From Green Park to Quay Street

Legacies of Jamaican enslavement in Manchester

by William Douch

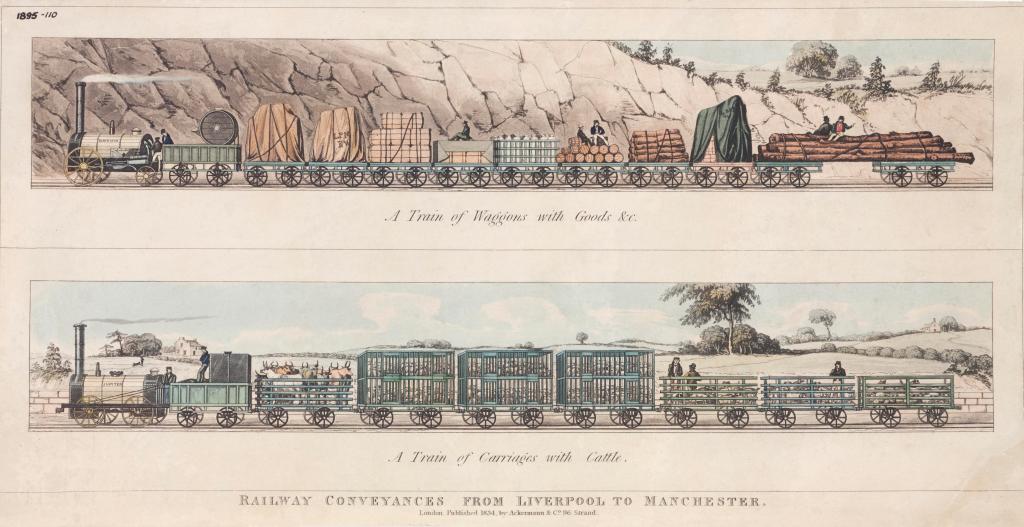

One of industrial Manchester’s many claims to fame is as home to the world’s oldest surviving passenger railway station and first railway warehouse. They were part of Liverpool Road Station, the terminus of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the world’s first inter-city line, which opened in 1830. The station and warehouse are now part of the Science and Industry Museum.

Science Museum Group Collection.

One of the major motivations for the railway’s construction was to speed up the movement of cotton from the port of Liverpool to the mills of Manchester and of manufactured textiles in the other direction. Much of this cotton was produced by enslaved people on plantations in the southern United States.

Science Museum Group Collection.

Merchants making their money from cotton, as well as people who profited from the ownership of enslaved people, were some of the key investors in the railway. Several important figures in the Liverpool and Manchester Railway received government compensation when Parliament abolished slavery in the British Empire in the 1830s, including Chairman and investor Charles Lawrence, Deputy Chairman and investor John Moss, as well as investors Robert Browne and Charles Turner.

Science Museum Group.

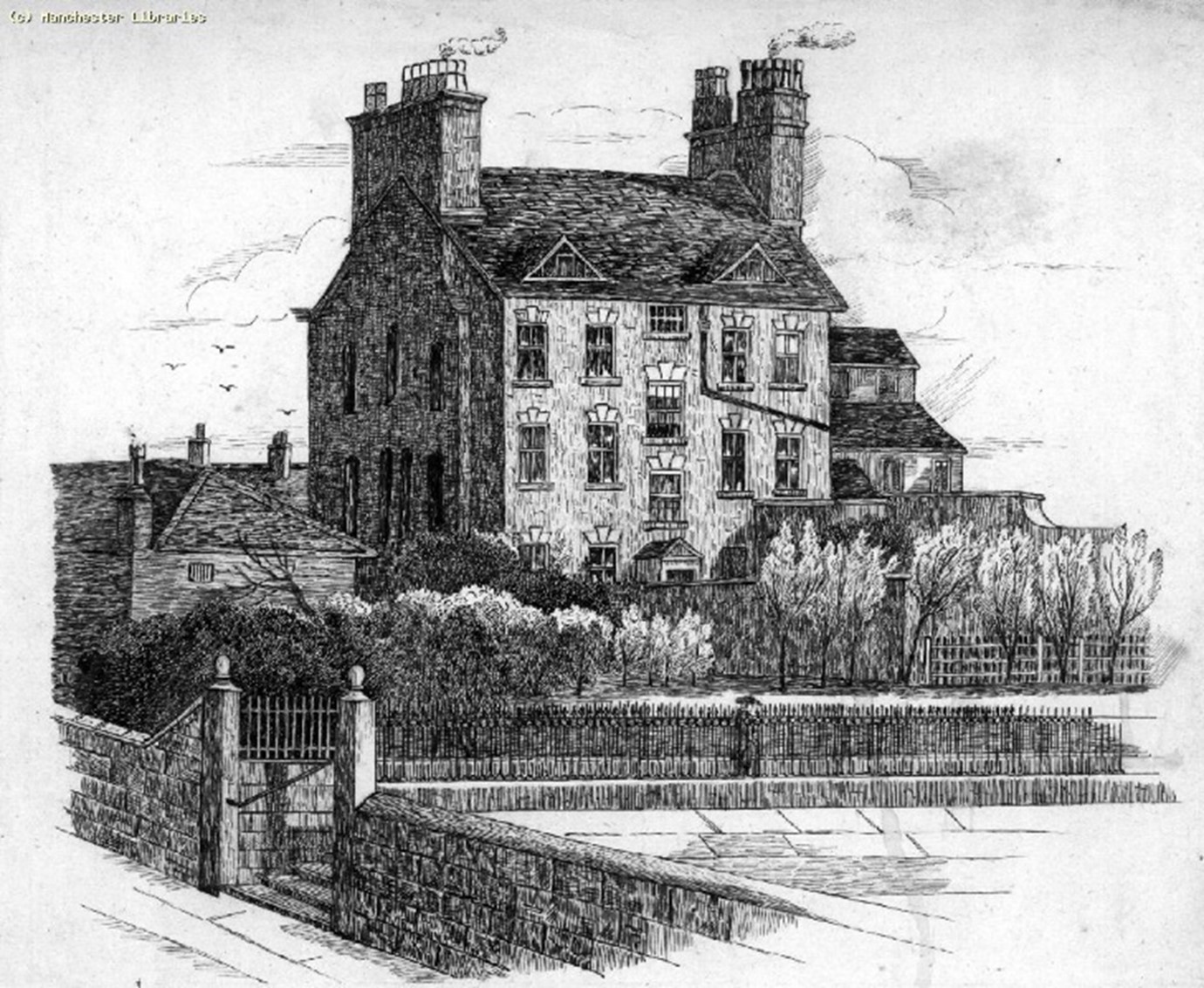

The land on which Liverpool Road Station was built was purchased by the railway company from the Byrom-Athertons, a wealthy Manchester family who had their own deep and lucrative ties to slavery. The vast proceeds of their two Jamaican sugar plantations sustained the lifestyle of one of Manchester’s wealthiest and most prominent female philanthropists, Eleanora Atherton, who lived just a stone’s throw away from Liverpool Road Station, in a house at 23 Quay Street, part of the family estate. Roads surrounding the location are today named Byrom Street, Lower Byrom Street, and Atherton Street.

ELEANORA ATHERTON’S HOUSE ON QUAY STREET.

One of Victorian Britain’s richest women, Eleanora Atherton used her wealth derived in part from Green Park Estate and Spring Vale Pen in Jamaica to support a variety of Manchester charities and institutions. Both plantations relied upon the forced labour of hundreds of enslaved people. This story explores the global threads connecting Atherton and her philanthropy in Manchester and the lives of those upon whose backs her wealth and privilege were built.

Charity in Manchester

Eleanora Atherton was born in 1782 and baptised in Manchester Cathedral. She was a descendant of two wealthy local families, the Byroms and the Athertons. She spent most of her life at her family home on Quay Street, with much of the rest of her time spent at her family’s country home, Kersal Cell in Salford.

Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives.

Some of Eleanora Atherton’s most notable charitable projects include a donation of £18,000 towards the construction of Holy Trinity Church in Hulme and funding for the restoration of the Jesus Chapel in Manchester Cathedral. She also supported many medical charities and hospitals, including St Mary’s Hospital and Manchester Royal Eye Hospital.

Through her philanthropy, Eleanora Atherton became a well-recognised Mancunian personality. She was often seen being carried around the streets in her sedan chair. Her donations to causes across Manchester meant she was remembered fondly, and her biographer Josiah Rose described scenes of mourning upon her death in 1870:

“There were no sincerer mourners than the poor inhabitants of that district, for almost each had some cherished memory of the kindly nature of “Madame Byrom”

Josiah Rose.

Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives.

Eleanora Atherton’s ownership of enslaved people

Eleanora Atherton’s philanthropy undoubtedly did much to help the people of Manchester, granting her a respected status in the city. Yet she derived significant wealth from her ownership of enslaved people and the plantations which she inherited in 1823 and maintained until the abolition of slavery, when she was compensated financially by the British government.

In the Slave Compensation Act of 1837, the British government paid out over £20 million to former slave owners, compensating them for the loss of people who had, until then, been considered their property. The government took out a loan to finance these payments, which was only paid off by British taxpayers in 2015. The formerly enslaved people of the British Empire received nothing in way of recompense.

Atherton received £2,543 for Green Park Estate, where 544 enslaved people had been held, and £866 for Spring Vale Pen Estate, where a further 182 enslaved people were held. Today that would amount to approximately £325,000. The total compensation for these two plantations was higher, but the money was split three ways between Eleanora Atherton, her brother-in-law, Richard Willis and his cousin, Joseph Fielden.

Courtesy of Michael M. Mosley.

Green Park Estate

Green Park Estate is located to the south of Falmouth, Jamaica. The property, established in 1655, was primarily used for cattle rearing until it was converted into a large sugar plantation in the 1760s. As production grew, a second sugar mill was constructed in 1773, alongside a stone windmill.

In 1832, Green Park held 555 enslaved men, women and children in forced bondage and labour, making it notable as one of the very largest plantations in Jamaica, where the median number of enslaved people held on a plantation was around 150. The workers’ village alone contained over thirty buildings.

Thanks to an estate journal from Green Park in 1823, we have rare access to an overview of the roles assigned to the enslaved population between 6 January and 10 January 1823:

Through a combination of the table above and registers of enslaved people that are available online, we can piece together some small understanding of family relationships amongst the people held on Green Park Estate. For example, under the ‘pregnant’ section, we can see that the number decreases and the number of ‘laying in’ increases by one. This shows us that one of the enslaved women gave birth on the Monday 6th of January 1823.

The slave register of 1823 records the ages of new children born into enslavement as well as their mother, which allows us to speculate the identity of the child born on the 6 January 1823, and their mother. In 1823, there were four children born to enslaved women at Green Park; David, whose mother was Ann Barrett, Charles, whose mother was Susan Barrow, Sally, whose mother was Sarah Campbell and Olive, whose mother was Peggy Richards.

The project and practice of enslavement has meant that we unfortunately have but small fragments of information documenting the lives of people held in bondage. Being able to link names and relationships to specific events and individuals therefore takes on important significance in rooting our understanding of Manchester’s connection to people whose experiences were otherwise actively erased by enslavers.

Life at Green Park

Green Park and large plantations like it across the Caribbean were a mixture between a large village or small town, an industrial-scale agricultural and manufacturing production compound, and a prison camp, where life, labour, activity, movement, and expression were monitored and controlled.

While Eleanora Atherton was enjoying her sedan chair rides around Manchester, the people upon whom her wealthy lifestyle depended were engaged in a wide range of forced labour. As we see from the task list, complex craft skills practised by enslaved men such as blacksmithing, masonry and carpentry were integral to the plantation’s operation. There were also many enslaved people, often women, who were required to take on domestic roles in the Great House, working in the kitchens, as maidservants, or as washerwomen.

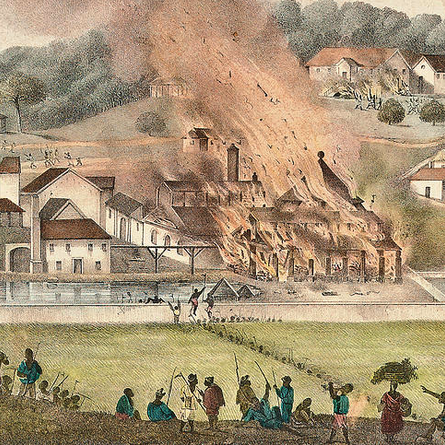

Slavery Images.

Most people enslaved on Green Park were forced into field work in a three-tiered gang system, where different tasks were given, dependent on physical strength. The first gang comprised of the field workers who were most physically fit, such as younger men and women. They were forced to do the most exhausting work, such as cutting the sugarcane. The second gang was made up of people who were no longer physically fit enough to do the most strenuous work, either through aging or injury. The third gang was made up of young children and older enslaved people who would typically take jobs that required lower physical strength but were nevertheless tiring and monotonous, like weeding.

“Among the unfortunate occurrences come to my attention, I must note a boy, who on the plantation Annaberg was put to throwing sugar cane in among the cylinders of the windmill, which through his carelessness grabbed his fingers and ground off his right hand. I amputated the arm immediately, and he is now, with the exception of the loss of his hand, quite well.”

Dr Feilberg in an annual medical report back to Copenhagen in 1836 from the Danish colony of St. John. Such injuries were common across all sugar plantations.

a sugar mill on a brazil sugar plantation.

Another item from the journal which attests to the harshness and brutality of sugar production was the number of enslaved people who were described as ‘invalids’ on Green Park. In 1823, there were 42 people listed in such a way, around ten percent of the entire population.

These people may have received injuries such as loss of limbs or had bodies broken through a lifetime of heavy, forced labour that meant they were incapable of working on physical tasks. In addition to this, there were 29 enslaved people listed as in the hospital and unable to work at the time, either through illness or injury.

The Green Park roster also demonstrates how plantation enslavement was underpinned by complex methods of control. Some roles that required responsibility for supervision or independent work could offer improved personal status and access to some privileges, such as better accommodation and rations, less physically demanding labour, greater freedom of movement, the gaining of valuable skills, and the rare potential of freedom for loyal service. Each gang included enslaved drivers and overseers, while we also can see 9 overseers and 30 watchmen listed with specific tasks.

Resistance

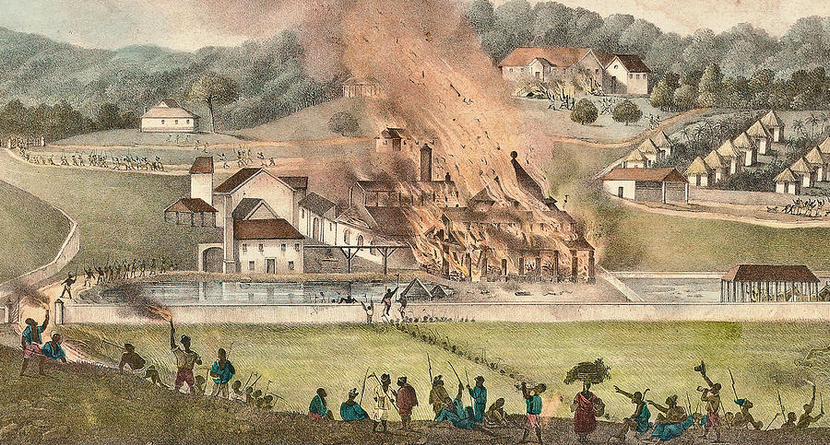

Resistance to enslavement took many forms, such as strategies to slow the pace and intensity of work or the destruction or theft of goods and produce by outsiders or people from the plantation itself. Attempts to escape control and supervision were common, such as meeting clandestinely with those from outside or within the plantation for social interaction and the exchange of information or goods, temporarily leaving the plantation to avoid work or punishment or running away. Enslaved and free watchmen were tasked with preventing such activities as well as raising the alarm when outright violence or rebellion took place.

Wikimedia Commons.

The main plantation house on the estate was equipped with a variety of different defences, in case of a Spanish or French invasion or a slave revolt, the latter of which was a constant threat. When Eleanora Atherton inherited Green Park, the strong legacy of the successful Haitian Revolution, which led to the collapse of slavery in the French colony of Saint Domingue and the establishment of the free Black republic of Haiti, both terrified enslavers and offered heart to the enslaved.

Led by Black Baptist preacher Sam Sharpe, the Baptist War, or Great Jamaica Slave Revolt, took placed over the period of eleven days after 25th December 1831, during Eleanora Atherton’s period as a slave owner. Demanding more freedom and payment for labour at “half the going rate”, it involved around 60,000 people, out of a total enslaved population of 300,000. Although eventually suppressed, the scale of the uprising and fear of further rebellions had a major impact on public and political opinion in Britain, hastening the abolition of slavery.

We have a first-hand account of the role of the enslaved Head Man at Green Park in defending the estate from external and internal threat, with the Cornwall Courier explaining that he “voluntarily mounted guard … for the purpose of protecting their master’s property from incendiaries”.

Legacies

Eleanora Atherton engaged in various acts of philanthropy that contributed greatly to the wellbeing of Manchester’s population and the growth of its medical and religious institutions, not to mention providing the land sold for the construction of the historic railway between Liverpool and Manchester.

These projects were considerably supported by the profits from the plantations her family had owned for generations, generated through the labour of the people enslaved there. Today, the Green Park Estate lies in ruins, but its legacy lives on in the economic and social benefits and built environment of modern Manchester and the stories of lived experiences and struggles for survival and resistance we are able to piece together from the scant historical remains.

Find out more

Online

London Reconnections, Slavery and the Railways, Part 1: Acknowledging the Past.

UCL, Legacies of British Slave Ownership Manchester and Slavery, Part 2.

Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, Eleanora Atherton.

The Last Great House, Green Park Sugar Estate The History.

Science and Industry Museum, First in the World: The Making of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

Books

Orlando Patterson, The Sociology of Slavery, 1969.

Christer Petley, Slaveholders in Jamaica, 2010.