John Owens’s Trade in Slave-Grown Produce

By Katie Haynes

This article is part of a series accompanying the Founders and Funders: Slavery and the Building of a University exhibition and is co-posted on the Rylands Blog.

During the 19th century, Manchester became the world’s first industrial city, at the centre of a global cotton-trading network. New transportation links such as the Bridgewater Canal linking Manchester and Liverpool meant that it became quicker and more profitable to transport raw materials from Liverpool to the factories and mills in Manchester.

Growing opportunities in Manchester meant rapid population growth with people migrating towards new employment opportunities in the factories and mills. Many entrepreneurs seized these opportunities to set up their own businesses which could reach across the world in their search for markets, materials, and profits.

One of those men was Owen Owens, who left North Wales for Manchester in the late 18th century with his wife Sarah. He was ambitious, like many of the young men who dreamed of elevating their social and financial position in the growing town. He set up a manufacturing business specialising in hats, furs, and umbrellas which his son, John Owens, joined in 1815.

A Changing Business

When John Owens joined Owen Owens & Son, the firm was well established, exporting and importing manufactured goods to the USA. Owens had forged connections in Philadelphia and New York by the 1820s which lasted decades. He had forwarding agents, lenders, and brokers to whom he consigned goods regularly. He predominantly shipped velvet, silk umbrellas, gingham, and shirts, to Philadelphia and New York. [1]

His letters also included instructions about what they should do with the items shipped to the United States to maximise profits from their sale:

“If you have not sold the lot of cotton, we shall thank you not to offer it at present we think rather more favourably than we did of this article and will hold a week or two longer”.

Slavery and the Cotton Trade

Owen Owens died in 1844, leaving the firm to John. By this time, he had given up manufacturing to invest much of his considerable wealth in the trading of slave-produced goods. He began importing cotton bales on a large scale from the US South. Invoices from the US show that he was mainly buying from Charleston, South Carolina; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Savannah, Georgia, the hubs of a rapidly-growing cotton empire. In these places, chattel slavery and cotton went “hand in hand”.

Cotton was grown and picked by enslaved Africans and African Americans on plantations. This was subsequently sold by planters to brokers, who then traded it to merchants, including John Owens. Invoices reveal Owens was purchasing between 50 and 300 bales on a regular basis. [2]

The amount of cotton that John Owens ordered depended on the state of the market. Letters from his brokers reveal the demand for cotton was constantly changing. Weather was a large factor which affected both the quality and quantity of cotton picked. Owens, like the many other Lancashire cotton merchants monitored supply, demand, and prices to ensure they purchased at the lowest price they could and waited to sell when the market prices were at their highest.

Tracing the Enslaved Communities who Grew Manchester’s Cotton

Bales of cotton were listed on the invoices with identification marks which would have been stamped onto the bales. These were used to trace which plantation or enslaver the cotton had originally came from. This was important because there were sometimes issues with the bales as one letter from John Owens to his broker reveals.

The letter establishes that there had been a complaint from Owens about stones increasing the weight of bales of cotton which had then increased the price, leading to losses in profit. Enslaved people would often resist the brutal pushing systems of picking and packing by adding stones to cotton bundles to reduce the amount of work they were forced into. [3]

Using these stamps, it has been possible to pinpoint a specific plantation where the cotton bought by John Owens was grown. This is because many plantation owners used their own initials as a trademark. One of these marks is by W.H Ellison.

William Harrison Ellison was an enslaver from a wealthy family in Fairfield County, South Carolina. Ellison’s plantation was one of the larger plantations in South Carolina with 94 enslaved people living there at the time of the 1860 Federal Census. The names of the enslaved people are not included, all that is shown is their ages and sex. [4]

The small mark within this letter highlights a direct link between the cotton John Owens was buying and profiting from and enslaved people in Fairfield County. Tracing any cotton shipment to a specific plantation is a very rare connection to achieve.

Through this ground-breaking original research we are able, however to establish a tangible link between the University of Manchester and a community of enslaved people whose forced labour was directly tied to producing the wealth that supported the foundation of our institution. While Owens did not own enslaved people, he was a part of an extensive and essential system which profited from slave-grown cotton in the United States.

Creating a Cultural City

Another of John Owens’ major ventures with cotton was a partnership with his friend George Faulkner. John Owens invested significant money in a mill built by Faulkner’s family business, Samuel Faulkner & Co. The proceeds from this investment funded helped to support Owens’ wealthy middle-class lifestyle. [5]

Personal receipts and private papers belonging to John Owens show that he spent much more than his father. John was subscribed to many up-and-coming cultural institutions based in Manchester. Institutions including the Manchester Natural History Society, the precursor of the Manchester Museum. [6]

Owens also subscribed to the Portico Library and News Room for which he paid annually at the cost of two pounds and ten shillings. Owens’ subscription to the Portico Library and News Room is notable as this was a subscription-based library and newspaper stockist for gentleman to read the latest news that had been shipped from London. Being a subscriber to this institution highlights John Owens’s status as a member of the wealthy business elite who fostered and funded the intellectual and cultural growth of Manchester as ‘the first modern city’ through profits deeply connected to slave-produced wealth. [7]

John Owens’s Legacy and the University of Manchester

John Owens final and most noteworthy legacy was the almost £100,000 that he bequeathed in his will (the equivalent of over £10 million today) following his death in 1846 to set up a college, under the premise that it would be open for young men regardless of their religion, class, or birthplace:

“The students, professors, teachers, and other officers and persons connected with the said institution shall not be required to make any declarations as to, or submit to any test whatsoever of their religious opinions”

This was a progressive and inclusive instruction as, until this period, attendance at English universities had been limited to those who were Church of England congregants, which excluded non-conformists and Catholics.

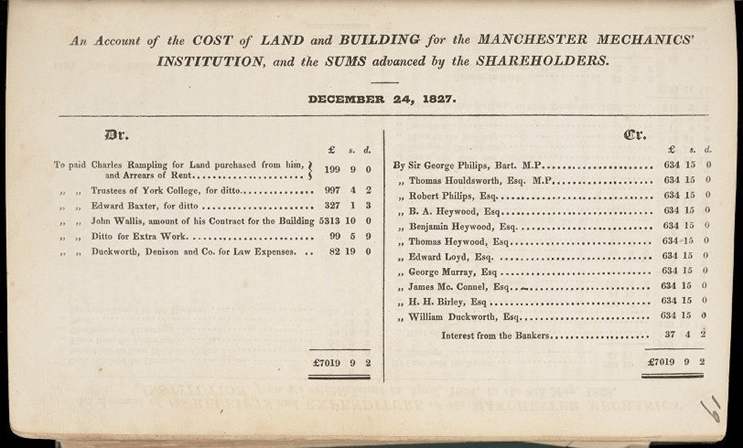

Established in 1851, Owens College was set up by the executors of his will, one of whom was his closest friend and business partner George Faulkner, who was head of a group of trustees who appointed teaching staff and planned the college’s aims, curriculum, and financial details. The College was managed in line with Owens’s will for nineteen years, demonstrating the influence that he held over the College, even in death. [8]

Owens College later became a part of the University of Manchester and the historic John Owens building stands at the centre of the University of Manchester campus, housing some of its key central administration and the Vice-Chancellor’s directorate. One of the university’s largest residential campuses in Fallowfield is named Owens Park.

While the creation of Owens College was ground-breaking, it is important to register that much of John Owens wealth was directly attributable to the importation of slave-grown goods, and, therefore, that the enslavement of people of African descent was central to the University’s foundation and part of the reason it exists today.

Notes

[1] B. W. Clapp, John Owens: Manchester Merchant (Manchester, 1965) –https://archive.org/details/johnowensmanches0000clap/page/n7/mode/2up

[2] Owen Owens & Son, Correspondence relating to North American and Canadian trade, GB 133 OWN3/2/3

[3] Owen Owens & Son, Correspondence relating to North American and Canadian trade, GB 133 OWN3/2/3/10

[4] The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Eighth Census of the United States 1860; Series Number: M653; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29, p. 189 – https://www.ancestry.co.uk/discoveryui-content/view/90843316:7668 (account required to access)

[5] B. W. Clapp, John Owens: Manchester Merchant (Manchester, 1965) –https://archive.org/details/johnowensmanches0000clap/page/n7/mode/2up

[6] Owen Owens & Son, GB 133 OWN1/7/3/4/3/

[7] “Portico Library, Mosley Street, Manchester”, Revealing Histories – http://revealinghistories.org.uk/who-resisted-and-campaigned-for-abolition/places/portico-library-mosley-street-manchester.html

[8] James N. Peters, “The campaign for a University of Manchester”, University of Manchester Special Collections Medium blog, 3rd December, 2020 – https://medium.com/special-collections/the-campaign-for-a-university-of-manchester-63f84974ede6

How to Cite

All of the articles linked to the Founders and Funders: Slavery and the Building of a University exhibition and research project are peer reviewed and fully-referenced works of original scholarship. Any material used in academic publications should be cited as such. we suggest this format:

Katie Haynes, “Our Founder & Fairfield County: John Owens’s Trade in Slave-Produced Goods”, Guest Blog – Global Threads Project, (Manchester, 20th September, 2023) – [https://wordpress.com/post/globalthreadsmcr.org/4471]

Read other posts from Founders and Founders: Slavery and the Building of a University:

Leave a comment