A Visitor in Lancashire

Gandhi, khadi and the decline of Lancashire cotton

by Sibia Akhtar

“I remember seeing him clearly. He was a funny little man and had old clothes on, he looked poor.”

Former mill worker, Ethel Gunning, aged 104 in 2011, recalling Gandhi’s visit to Lancashire in September 1931.

When Gandhi arrived in Darwen to adulation and cheers in late September 1931, at the height of economic crisis, his simple clothing was the source of much comment and interest among the crowds of working class Lancastrians. He was wearing khadi – traditionally hand-spun and woven textiles, of a type crafted in South Asia for centuries.

Industrially-produced cotton was one of the driving forces behind British colonisation, therefore home spun cotton was taken up by the anti-imperial movement as a powerful symbol of resistance to economic domination, with Gandhi describing it as “an appeal to go back to our former calling”. Prior to colonisation, India had been the global leader in cotton textile manufacturing but British authorities had followed policies which suppressed industrial development and production – creating a vital market for cloth exports and jobs for Lancashire’s workers.

Science Museum Collection. Find out more here.

While British-made textiles dominated the mass market in India, centuries-old domestic craft traditions continued in rural areas as a way of providing homemade clothing, generating income, and as a leisure activity. Products ranged from simple plain cloth to colourful or intricate patterns with many regional differences which “communicated a variety of social messages, ranging from community identification to political deference”.

Gandhi put great effort into travelling across the subcontinent during the 1920s to build a mass movement for the spinning of khadi as a way to provide additional employment and incomes in rural areas almost wholly dependent on agriculture. The khadi movement politicised the fabric as one which united the nation to strive for self-rule.

Wikimedia Commons.

It was a vital part of the wider Swadeshi movement which sought to establish India’s autonomy from Britain as the basis of self-government and harness the power of Indians as consumers to hit at the economic heart of the imperial system. Gandhi fully embraced the philosophy, choosing to permanently adopt khadi as his form of dress and making spinning central to the daily routine of the community at his ashram in Sabarmati, Gujarat.

Decline to crisis

In 1913, Lancashire remained a global powerhouse of cotton production. British-controlled India was a key market, purchasing 60% of Lancashire’s products, supporting hundreds of thousands of jobs. While Britain’s economy suffered during and after the First World War, competitors in places like the United States, Japan, and India were merging into larger, more profitable corporations and investing in new technologies, techniques, and working practices that Lancashire’s mills could not afford.

Further pressure came when India’s government used its limited powers to protect local producers by placing tariffs on imported cloth in 1922. This steady decline turned to crisis after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which triggered a worldwide Great Depression.

STRIKING MILL WORKERS IN BLACKBURN, 1920.

This acute crisis backdrop presented an opportunity to build on decades of organising across India and force the British government to the negotiating table. Gandhi’s Congress Party organised a coordinated programme of anti-imperial civil disobedience, with millions of people taking part in rent strikes, refusals to pay colonial taxes on essential products, and renewed boycotts against a range of British imports – most prominently, cotton cloth.

Wikimedia Commons.

Across the UK, industrial and mining areas were most impacted by the collapse in global trade, with British exports falling by 50% between 1929 and 1933 and unemployment rising from 1 million to 2.5 million. Despite long decline and a global recession, the Indian boycott was seen as a direct cause by many for the scale of suffering in Lancashire.

As the crisis dragged on and Lancashire unemployment soared, tensions and hardship grew. 8,000 people attended a meeting at Blackburn Town Hall in April 1931 and angrily heard that: “Hostility to Great Britain and particularly to Lancashire … [had been] cultivated beyond all economic reason.”

Working Class Movement Library.

The boycott campaign gained Gandhi a place at the Round-Table Conference on Indian self-government in London in September 1931, where the press carried daily updates on his activities and speeches. Speculation and excitement about a potential visit were rife ahead of confirmation that he would accept the invitation of the Davies family of mill-owners to spend the weekend of 25th-27th September in Lancashire.

In the days before the visit, the situation was very volatile. Over 10,000 people were unemployed in Darwen alone. Anger flared at mills in Burnley and Glossop as some workers decided to break picket lines and work at reduced rates. As Gandhi arrived in Lancashire, the new Labour leader Arthur Henderson was speaking to a crowd in Burnley demanding an election and radical economic policies.

Hopes were high among many workers that the visit would result in improvements in employment, as Ruth Boardman, seven at the time, recalled her mother explaining: “We’re going to see a very important man from India and he’s going to make things better, we think, with the cotton trade.”

Khadi in Lancashire

“Mr. Gandhi was dressed then as he has been dressed since, bare-legged with sandals, and wearing an unbleached quilted wrap over his usual white cotton. Such details of appearance and incident have been the main topic of conversation in Darwen, and serve to indicate the enormous interest which is taken in the visit.”

Manchester Guardian, September, 1931.

Wikimedia Commons

Khadi, and the philosophy and economic policies it represented, was central to Gandhi’s message. He took pains with each of his audiences to explain that through his appearance, “he wished to appear as faithfully as could be as the representative of the teeming and naked millions . . . he would consider himself indecent if he took a yard of cloth beyond [those] physical requirements”.

While much remarked at the time, the unusual image stuck in the minds of those who saw him, often more clearly than the political details of his trip, as Ruth Boardman and Dorothy Donelan recalled decades later:

“This little man came on and I looked at my mother and I said:

‘Which is Gandhi mother?’

She said: ‘He’s that man there.’

I said: ‘He’s not an important man, he’s a poor little man, he has no clothes on’.

He had sort of a white-type cloth between his legs. It was like a big nappy! And then this thing around his [shoulders] . . . was hugged round him . . . he had nothing on his feet, only a pair of sandals . . . I was horrified.

I said: ‘He’s no shoes on mother!’”

Quoted in BBC documentary Empire. Watch video here.

Wikimedia Commons.

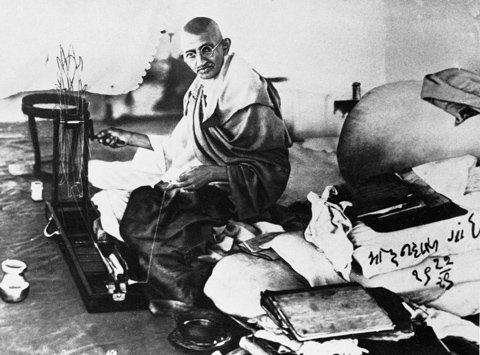

Throughout his time in the UK, Gandhi continued his daily practise of hand spinning – indeed, there was a great rush before his train left London for Lancashire when it was realised that part of his wheel had been left behind!

Image courtesy Bow Arts Trust Raw Materials project. Find out more here.

“Mr. Gandhi was seated on the floor on some cushions throughout the conversations, with his spinning-wheel in front of him . . . He spun on the wheel during some part of the afternoon, to the curious interest of the others who sat on chairs grouped round him.”

Manchester Guardian, September, 1931.

While his audience may have found it curious and unusual, the impact of Gandhi explaining the significance of the khadi movement and his reasons for the boycott whilst embodying it with his spinning and clothing made a deep impression. After his meeting with owners and trade unionists at Edgworth, one official, John Lee, stated: “We all felt that from the idealistic point of view we could not quarrel with Mr. Gandhi. I myself said to one of my colleagues, ‘If I were an Indian, I should be a discipline of Gandhi.’”

Reception

“The police had been in the previous day to check there were no nooks, or crannies, where people could hide and take a pot shot at him . . . He was a brave man to come because there was a lot of ill feeling in the town at the time.”

Sigrid Green, whose father worked in a mill on Crown Street, Darwen, was 11 at the time of the visit.

“There was a lot of excitement about his visit. It was quite something for Darwen, and we made him very welcome, even though there were a lot of people not so pleased about what he was doing.”

Ethel Gunning, former mill worker, Lancashire Telegraph, 26 September, 2011. Read full text here.

gandhi meeting crowds in darwen.

With such great hardship and tensions fanned by months of claims that the boycott was the main cause of poverty and unemployment, there were genuine fears that Gandhi might be the subject of violence, with police escorts put in place for his journeys. In fact, he was met with great adulation and not a little curiosity as footage and photographs of his time in Darwen show. You can view archive video of Gandhi’s visit to Lancashire at this link

“My father said I want you to see Gandhi, then in the future you can say that you witnessed that brave man.”

Gusta Green, BBC News, 23 September, 2011. Read full text here.

For the crowds of people who turned out in Darwen this was truly a once-in-a lifetime occasion. Seeing, and even meeting, a figure of such immense global stature and respect left a lasting impression on the town and its people.

Enlightenment without hope

“The poverty I have seen distresses me and it distresses me further to know that in this unemployment, I have also some kind of a share. That distress is relieved, however, by the knowledge that my part was wholly unintended; that it was a result of the steps that I took, and had to take, as part of my duty towards the largest army of unemployed to be found in the world, namely, the starving millions of India, compared with whose poverty and pauperism the poverty of Lancashire dwindles into insignificance.”

Manchester Guardian, September, 1931.

While he listened with patience and showed sympathy, Gandhi’s intentions in visiting were to convey his message and philosophy in person, increase understanding, and reduce tensions, not to change policy. The best he could do was to repeat an offer of preferential treatment for Lancashire above other international suppliers if the British government would give India full power over its own tariffs, trade, and taxation. It was clear that there was little chance of much more.

Wikimedia Commons.

While hopes may have briefly been raised for a rise in trade, much local opinion was quite frank and resigned post-visit. The Blackburn Northern Daily Telegraph frustratedly reported their “Cold Comfort from Mr Gandhi” with what they regarded as “ordinary trading relations” unlikely to return. The Darwen News was equally blunt when it summed up the impact of the visit being that: “Mr. Gandhi has seen Lancashire, and Lancashire has seen Mr. Gandhi, and there is the end of it”.

The words of trade unionist F Hindle after one meeting neatly summed up the outcome of the whole visit:

“There was no bitterness, and the interview was a pleasant one. All the same, I think it had brought home to us the fact that we cannot hope for the same volume of trade with India again. I don’t like saying that, but we must face facts sometimes . . . it has brought enlightenment, but it is enlightenment without hope.”

Manchester Guardian, September, 1931.

The realisation that there was little to be done to sway Gandhi’s policy indicated an acceptance of the shifting of imperial power relations. Britain would no longer be able to dictate economic relationships solely to its own advantage.

Khadi today

Despite the continued growth of industrial textile production in South Asia post-independence, khadi retained its role in continuing to provide additional incomes in rural communities. The centrality of the principles of the Swadeshi movement to achieving independence were recognised with the enshrining of the spinning wheel on the flag of newly independent India.

© Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Find out more here.

The Indian government continues to run the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) while Bangladesh saw a resurgence in popularity of khadi production following its independence from Pakistan, with Bangladeshi muslin gaining international status for its unique quality and heritage.

Khadi is now regarded as desirable high fashion, helped by its reputation as a fabric with attitude and radical meaning. In 2017 460,000 people in India were employed in its production. It can be made with cotton, silk, and wool, and its handmade nature means the material can be designed to be comfortable and lightweight.

© The Whitworth, The University of Manchester. Find out more here.

A major driver behind Gandhi’s identification with and embracing of home-spun fabrics was his understanding of the deep linkage between industrialisation and colonisation. The link between the social responsibility of the khadi movement and environmental justice, and the focus on small scale, sustainable rural development that supports traditional communities and reduces reliance on mass-produced goods means that the cloth and its Gandhian philosophy offers renewed significance in the era of climate change and over-consumption.

Mapping gandhi in lancashire

This study, “A Visitor in Lancashire”, takes its title from a headline in the Manchester Guardian, which produced detailed, blow-by-blow coverage of the visit.

In the map below trace Gandhi’s itinerary by using the Manchester Guardian’s reporting to follow his activities and locations visited during his landmark trip.

You can view a more mobile-friendly or full-screen version of the map here

Find out more

Online

Cotton Town, Mahatma Gandhi.

Working Class Movement Library, Gandhi in Darwen, September 1931.

Victoria & Albert Museum, The Fabric of India.

Books

Giorgio Riello, Cotton: The Fabric that Made the Modern World, 2013.

Mary B. Rose, The Lancashire Cotton Industry A History Since 1700, 1996.

Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton a Global History, 2015.