cloth, clothing and apprenticeship in the british caribbean

This article draws on research supporting the co-curation of The Penistone Cloth: Textiles and Slavery – From the Pennines to Barbados and Beyond exhibition held at Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery as part of the British Textile Biennial

The histories of ordinary, day-to-day items can lead us to uncover previously obscured narratives of resistance, resilience, and innovation. From the looms of Yorkshire weavers to plantations across the Caribbean, the story of penistone cloth highlights numerous transatlantic threads connecting places and people. These allow us to uncover vivid insights into the lives of just a few of the millions who wore these fabrics daily.

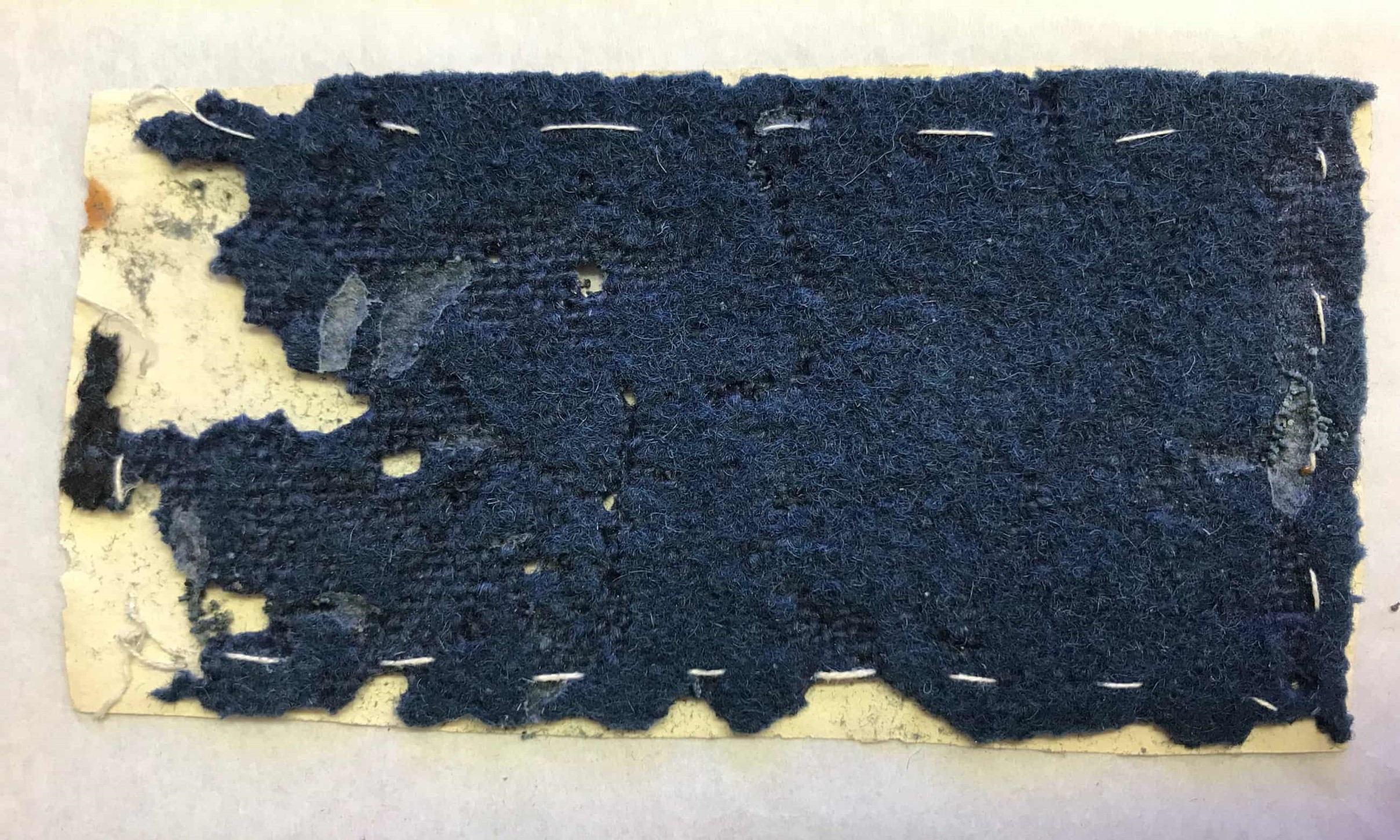

While cotton is perhaps the fabric most associated with the Industrial Revolution, until the 1790s wool was Britain’s predominant textile industry – with production growing 800% from 1700 to 1800. This blog will focus on the example of penistone (or pennistone) cloth, a type of coarse, heavy wool hand woven in the region around the West Yorkshire town of the same name.

Significant demand for these cheap, low-quality fabrics came from the Americas. Here, it was imported in bulk to clothe the enslaved populations forced to cultivate the raw materials and produce supplying and enriching Britain. Firsthand accounts of formerly-enslaved people’s experiences reveal diverse and resourceful uses for these fabrics.

Slavery and Clothing on Sugar Plantations

“I saw a woman with a sucking child, but I don’t know where she came from. When she went out to work in the gang, she tied the child to her back, and put it under a tree when she got into the field. If it rained, she was allowed to stand aside and shelter it with her pennistone cloak.”

Excerpt from the account of Jeannette Saunders, an apprentice on Orange Valley Plantation, Jamaica.

Jeannette Saunder’s account not only speaks to the widespread presence of penistone cloth across sites of British slavery, it also reminds us how intimate the connection between enslaved lives and the Pennines was. Not just as the fabric that clothed the bodies of millions, but down to their use for the sheltering of babies whilst their mothers were forced into heavy labour.

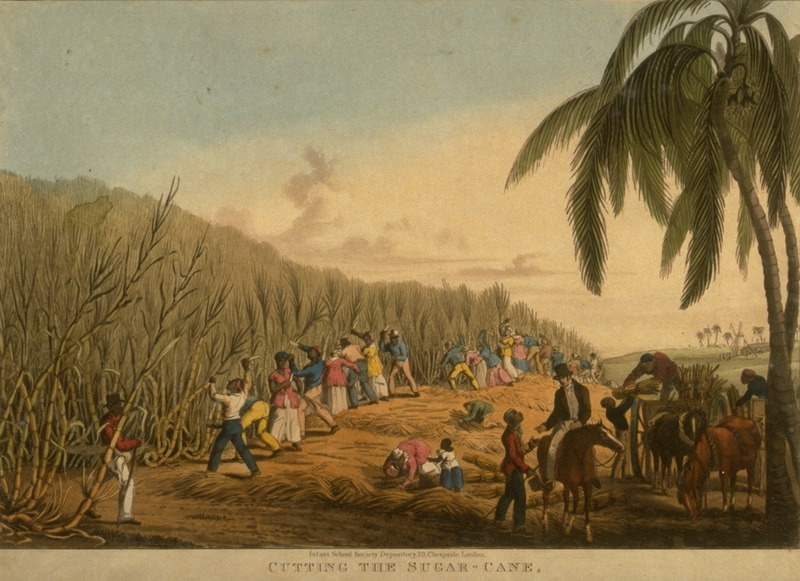

Throughout the 18th century, a series of technological and agricultural developments, combined with the vast-scale enslavement of millions of trafficked Africans, allowed the sugar industry to flourish across the British Caribbean. Sugar plantations were notable for their barbarity, with exhaustion, malnourishment, disease and violence rampant.

Slavery Images.

On several islands, including Jamaica, planters were legally required to provide clothing for their enslaved workers. These regulations ensured that enslaved Africans were dressed to the rigid European standards deemed ‘civilised’ by white colonialists. As the populations of enslaved people expanded, laws relaxed to simply mandate basic quantities of clothing, rather than specific garments.

By the end of the 18th century, planters had generally begun to import cheap fabrics (such as the penistone referenced by Janette Saunders), along with the tools required to sew them. Other fabrics commonly imported from across the United Kingdom and Ireland to clothe enslaved people included osnaburgs, Welsh plains and Irish linens.

The task of sewing fell to enslaved women, who were expected to perform household and childcare duties in addition to heavy fieldwork. Clothing provisions were consistently inadequate for the extreme labour and tropical environment, so supplies were often supplemented by trading at markets. Despite the enormous deprivation imposed by planters, this allowed enslaved women to carve out small freedoms in expressing their individuality, creativity, and African heritage.

Emancipation, Apprenticeship and the Workhouse

“Mr. Drake told Jenkins to cat [whip] us well, if we did not keep the step, as busha [overseer] sent us to be punished. One day, while I was dancing on the mill, I fainted on it, and dropped down. My hands dropped out of the straps and I fell down to the ground. I did not know anything of it myself until next morning, when my friends told me that I had fainted, and that they were obliged to burn pennistone and put to my nose to restore me.”

Excerpt from the account of Betty Williams, an apprentice to Hiattsfield, in Jamaica.

Betty describes being revived by a piece of burning penistone cloth, having faced extreme violence in the workhouse. While the use of penistone as a type of clothing is something we would expect, this unique account suggests another, more ingenious, use of the textile, that may well have been a widespread and well-known practice.

In 1833, the Abolition Act was finally passed, outlawing slavery across British colonies. However, new systems of oppression would rapidly emerge. In Jamaica, between 1834 and 1838, freed people were still legally tied to their former enslavers as ‘apprentices’.

While planters were forbidden from privately punishing their apprentices, these institutions had been introduced as a “fairer”, state-sanctioned method of punishment. As the flogging of enslaved women (and consequent exposure of their bodies) was deemed particularly objectionable by abolitionists, women were especially likely to be sentenced to the workhouse for alleged misdemeanours.

Betty’s account illustrates the brutality that apprentices continued to face under this system. The contraption she recounts was a penal treadmill: a method of punishment by hard labour, that was also used throughout British prisons. The wheel was turned by prisoners continually stepping upwards, while strapped to (or holding onto) a bar. Flogged from below to keep up pace, the prisoners were said to “dance” on the mill.

While Betty was fortunately revived with the aid of burning penistone, at least thirteen workhouse deaths were reported in Jamaica throughout this era — it is likely that many more unpublicised deaths also occurred. In one case, a woman named Louisa Beveridge died after being strapped to the mill by her upper arms. This was her punishment for refusing to cut sugar cane, in protest of poor working conditions on her plantation.

Janette and Betty’s stories, drawn from mentions of penistone cloth in accounts given by formerly enslaved people, reveal firsthand the experiences of African and African-descended people forced to labour on British-owned plantations. Despite daily attempts by planters and the state to exploit, dehumanise and oppress, enslaved and apprenticed, these incidents are two rare surviving examples of how people made creative use of their extremely limited resources.

Find out more

Online

History of Science in Latin America and the Caribbean, Slavery and Science (1500-1888)

Articles & Books

Henrice Altink, ‘Slavery by Another Name: Apprenticed Women in Jamaican Workhouses in the Period 1834-8’, Social History (326:1), 2001

Steeve O. Buckridge, The Language of Dress: Resistance and Accommodation in Jamaica, 1760-1890, 2004.

Diana Paton, No Bond but the Law: Punishment, Race, and Gender in Jamaican State Formation, 1780–1870, 2004.

James Williams, A Narrative of Events Since the 1st of August, 1834.