This article draws on research supporting the co-curation of The Penistone Cloth: Textiles and Slavery – From the Pennines to Barbados and Beyond exhibition held at Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery as part of the British Textile Biennial

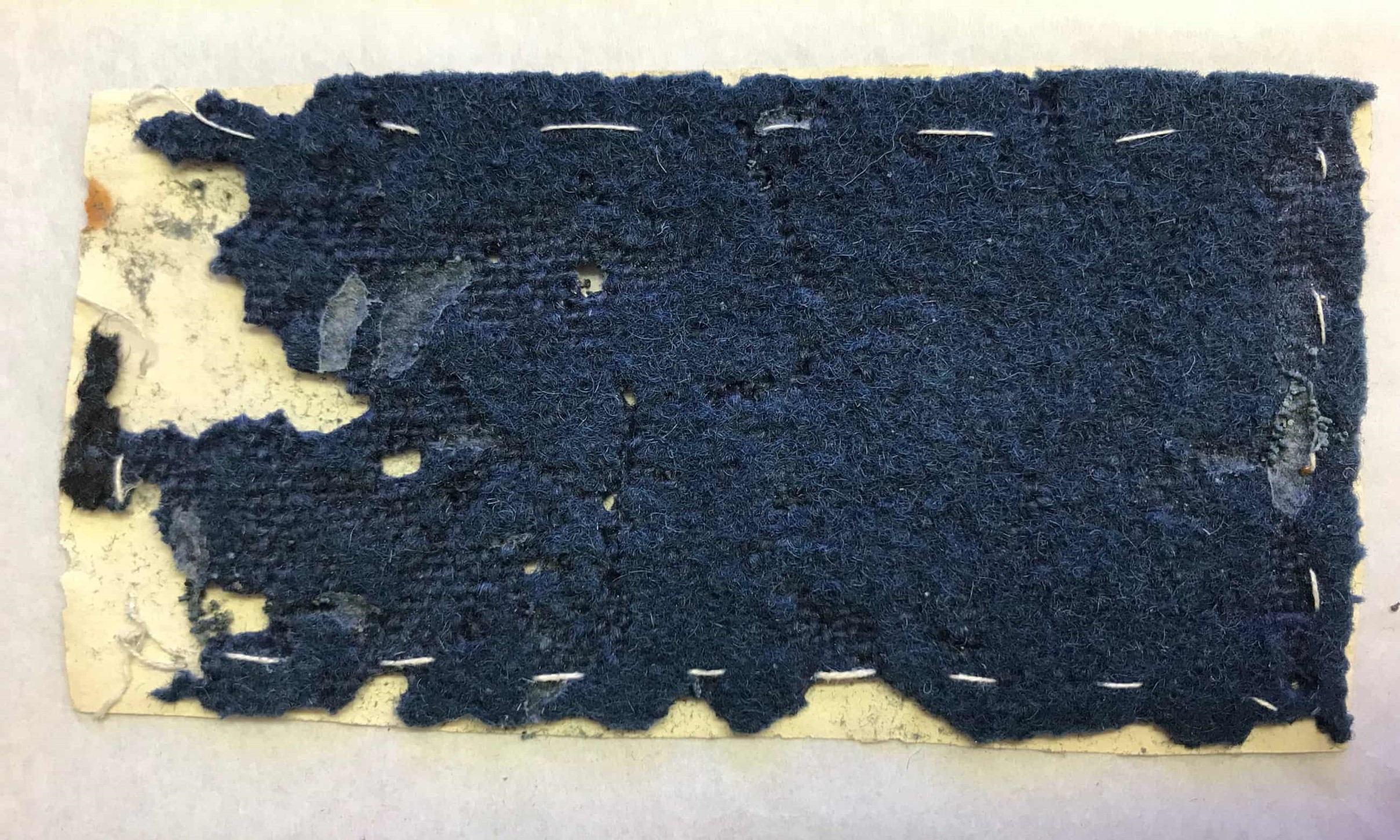

The Yorkshire-made penistone cloth is a rare surviving example of the type of cloth worn by enslaved people in both the Caribbean and North America, offering a tangible link through which we can explore and understand the significant role that clothing played in the lives of those held in slavery. Clothing was controlled through laws to limit expression, while runaway slave adverts intimately show links between Pennine-made cloth and the contestation of the bounds of slavery by freedom-seekers.

This blog delves into the world of clothing for enslaved people in North America through the 1735 South Carolina Negro Act and individual stories of enslaved women, exploring its multifaceted significance and the enduring impact of this aspect of their daily lives.

Control – One of the Badges of Slavery

“I have a vivid recollection of the linsey-woolsey dress given me every winter by Mrs. Flint. How I hated it! It was one of the badges of slavery.”

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, 1861.

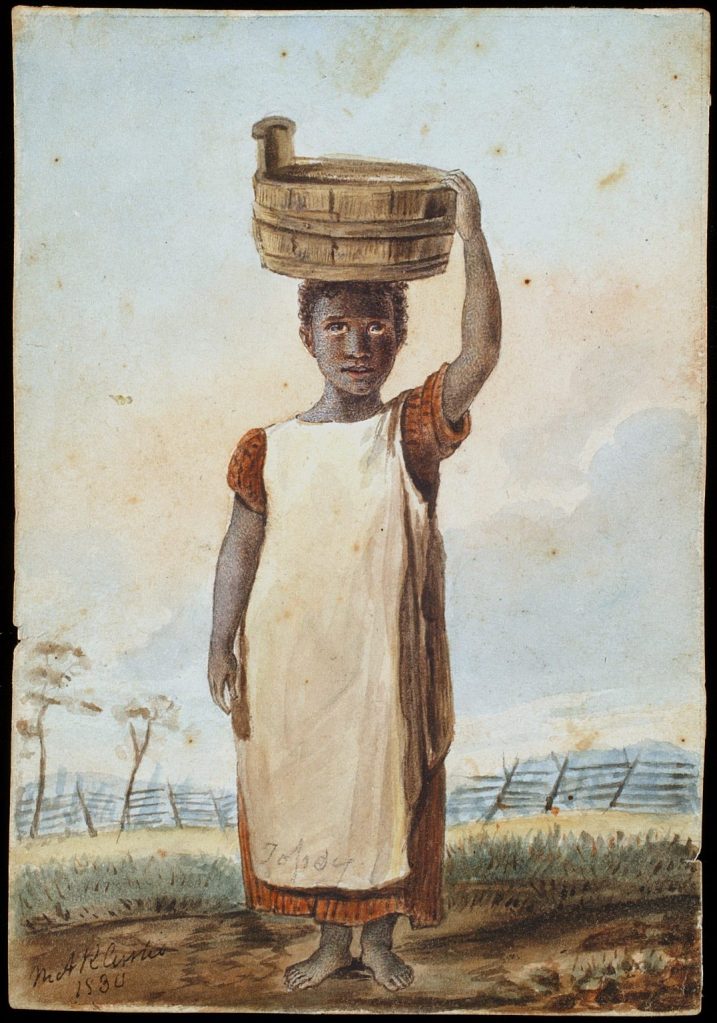

The clothing worn by enslaved individuals bore witness to the extreme hardships they endured. Many had to make do with clothing that became worn and tattered, usually made from cheap, coarse, itchy cloth including penistones made in West Yorkshire, osnaburgs, originally made in Germany, or Welsh plains. This cloth was supplied to enslaved people by their enslavers.

In the dehumanising and oppressive environment of slavery, clothing emerged as a symbol of identity and cultural heritage for enslaved individuals. Individuals confronted the challenges of a racially biased society that sought to marginalise them within American culture.

They aimed to demonstrate their distinct identities by customising their attire, a strategic act of defiance against slavery rooted in racism. Often, these individuals deliberately opted for and adorned themselves in stylish Euro-American clothing, a form of resistance aimed at challenging the racially-exclusive fashion norms prevalent in colonial society and the post-independence United States.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Reacting to these practices, rules regulating clothing for the enslaved were enshrined in law. The South Carolina Negro Act of 1735 decreed that enslavers should only give their enslaved workers clothing made of the cheapest and coarsest cloth.

The issue of the Carolina laws stemmed from concerns over enslaved and free black individuals crafting and wearing clothes that surpassed those of some white counterparts, notably poorer individuals and apprentices. This practice challenged the established system of racial hierarchy they sought to maintain. Additionally, these laws aimed to deter theft of superior fabrics by restricting their public use, thereby preventing their appropriation in defiance of established social norms.

“That no owner or proprietor of any Negro slave, or other slave, (except livery men and boys) shall permit or suffer such Negro or other slave, to have or wear any sort of apparel whatsoever, finer, other, or greater value than Negro cloth, duffels, kerseys, osnabrigs, blue linen, check linen or coarse garlix, or calicoes, checked cottons, or Scotch plaids…”

Excerpt from Clause XL, An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing Negroes and Other Slaves in This Province, 1840.

These garments provided minimal protection from the harsh elements of southern North America, where enslaved people faced both searing heat and biting cold. Enslaved people were responsible for making and repairing their own clothing with limited resources. They used discarded scraps of fabric and other materials to create or mend their garments.

Often, they had to trade or barter for cloth and sewing supplies, as their enslavers typically provided the bare minimum for survival. Written and oral records show that children and the elderly received the poorest quality of clothing due to not having to work as much out in the open, so were given clothes as and when needed rather than seasonally like adults working in the field.

Contestation: Freedom Seekers in Pennine Cloths

Clothing was intimately connected to acts of resistance carried out by enslaved people in practical as well as symbolic ways. There were many enslaved women who dared to seek freedom from the harrowing institution of chattel slavery. Enslavers would send out “runaway adverts” to local newspapers that had intricate details of what fugitive enslaved people looked like and what they wore.

When courageous 20-year-old Jenny escaped from enslavement in Philadelphia in 1782, her enslaver submitted an advert to the Philadelphia Journal and Advertiser appealing for help to locate her. The advert stated that she “took with her a bundle of cloaths”. We can imagine Jenny taking everything she owned as she planned her escape, ready for a fresh start. Jenny would have had to meticulously plan every step and be prepared for harsh weather conditions, thus having many clothes would have been an important form of protection.

Many more of the runaway adverts on the Freedom on the Move Database detail the clothing and fabrics that individuals wore when they escaped, with many references made to penistone cloth. Enslaved woman Sal, aged 28, who ran away in New York in 1766, was wearing:

“A Purple Calico Gown, a striped Cotton short ditto, a purple and white Calico Joseph, an old plain Gown, a blue quilted petticoat, a green Penistone ditto, a red shirt Cloak, & a black Silk Hat.”

There are also records of enslaved men running away wearing clothing made of penistone cloth, including 45-year-old Claus, who ran away in Philadelphia in 1741 wearing “a brown Kersey Wastecoat lined with red Peniston.” A fiddler, he carried his fiddle and bow with him, which, according to the advert, he played left-handed. John Jennings, who escaped in Maryland in 1746 wore “ a blue Penniston jacket”, as well as an ‘Irish Linnen shirt”.

While the history of penistones and other British-made “slave cloths” is one linked to dehumanizing practices, following these textiles on the backs of freedom seekers also allows us to see their connection to parallel stories of contestation – agency, resistance, individual experience, and self-expression.

Penistone’s inclusion in these runaway advertisements suggests its significance in the wardrobes of enslaved individuals. Moreover, the variety of other fabrics mentioned in the adverts, such as calico, osnaburg, and chintz, reflects the complex tapestry of textiles that played a role in the daily lives of those seeking freedom. Each fabric carried its own history, cultural associations, and practical uses, shaping the identities and experiences of the individuals involved.

From the restrictive laws dictating the types of fabrics allowed to be worn to the resourcefulness exhibited in crafting and adapting garments, clothing played a multifaceted role in the daily struggles of those enslaved.

The enduring impact of these clothing choices echoes the strength and determination of enslaved individuals to assert their identities and challenge the dehumanising institution of slavery. Through their clothing, these individuals left an indelible mark on history, highlighting the profound connection between personal expression and the fight for freedom.

Find out more

Online

Katherine Gruber, “Clothing and Adornment of Enslaved People in Virginia”, Encyclopedia Virginia, December 2020.

Marta Olmos, “Clothing, Identity and Agency in 18th Century Enslaved Communities“, History, but make it Fashion, June 2020.

Katie Knowles, Fashioning Slavery: Slaves and Clothing in the U.S. South, 1830–1865, PhD Thesis – Rice Fondren Library, 2014.

Books

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, 1861.