Culture, Cotton, and Wealth

The Manchester Athenaeum in 1859

LISTEN HERE TO THIS CASE STUDY READ BY THE AUTHOR

This article draws on research supporting The Warp / The Weft / The Wake by Holly Graham

A UAL 20/20 artistic commission working in partnership with Manchester Art Gallery.

As a freelance writer and researcher committed to social justice, I am always looking for meaningful work that aligns with my values. The aims of this research opportunity resonated with me, and I was delighted to be able to support artist Holly Graham’s work with Manchester Art Gallery as part of the 20/20 Programme.

Centred around African American abolitionist campaigner Sarah Parker Remond’s renowned 1859 speech at the Athenaeum (now part of Manchester Art Gallery) my research focus felt like a valuable opportunity to shed light on often forgotten chapters in Britain’s legacy of slavery.

What I found not only allows us to understand more holistically the Athenaeum’s role and functions as an institution, and the centrality of the cotton industry to its existence and activities, it also shows that competing visions of Manchester’s cultural life and its relationship to the dark sources of its wealth, issues which we continue to grapple with today, have a history as old as the Athenaeum itself.

Cotton and Culture

I was tasked with building a rich picture of the Athenaeum at the time of Remond’s lecture. I wanted to create an understanding of the type of events, meetings, speeches, and activities the institution was home to, and the people who hosted and frequented this space, thereby piecing together an understanding of the type of circles Remond would have found herself in in 1859.

the MANCHESTER athenaeum BUILDING, erected in 1838.

The building was constructed in 1838 as a clubhouse for the Manchester Athenaeum, a society which had been founded three years earlier for the ‘advancement and diffusion of knowledge’. By scouring Manchester newspaper archives from 1859 and surrounding years for mentions of the Athenaeum, I was able to piecing together a patchwork picture of the multitude of uses of the space, and the lives it was intertwined with.

Lectures at the Athenaeum spanned topics from female hygiene and education to the American Civil War. Not only was it the site of Remond’s anti-slavery lecture, which was so popular people had to be turned away, the institution also hosted a celebratory banquet for Lord Palmerston and Captain Denman in 1859. Palmerston and Denman (who was Captain of the Royal Navy’s slave-patrolling West Africa Squadron) had returned from an anti-slave trade mission in Brazil, which Palmerston described as “successful” in suppressing “the detestable and diabolical crime, slavery” to a crowd of 200 Athenaeum members.

The space was also home to a wide array of clubs and societies. A gymnastics society met in the Athenaeum’s very own gymnasium, and the building also hosted a chess club. Athenaeum members could join a range of societies including essay and discussion, dramatic reading, and instrumental music, as well as a selection of European languages clubs. The Athenaeum was also home to a newsroom with an electric telegraph and a library with more than 15,000 volumes.

It was not uncommon for other organisations to hire out space in he building their meetings. For example, The Manchester Warehousemen and Clerks Provident Association, many of whom would have been in the city’s textile industry, held their quarterly meeting in the Athenaeum in January 1859.

My research was driven by an interest in Manchester’s legacies of slavery, and how these often-silenced connections – thinking primarily about the transatlantic cotton trade – underpin British institutions. The Athenaeum was founded and governed by Manchester’s male elite to cultivate high society interests.

The institution was dedicated to the procurement of knowledge, and to the development of artistic, literary, scientific excellence to enhance the city’s cultural life and make it accessible to any citizens who could afford a membership or admission fee.

It was also an institution entirely steeped in cotton. Many of its wealthy governors made their money from the textile industry and underpinned the Athenaeum in the form of sizeable donations and membership subscriptions. It was also an important space in the commercial life of the textile trade, hosting the bankruptcy court where closing cotton businesses had their mills, equipment, and materials sold to new owners.

British Newspaper Archive.

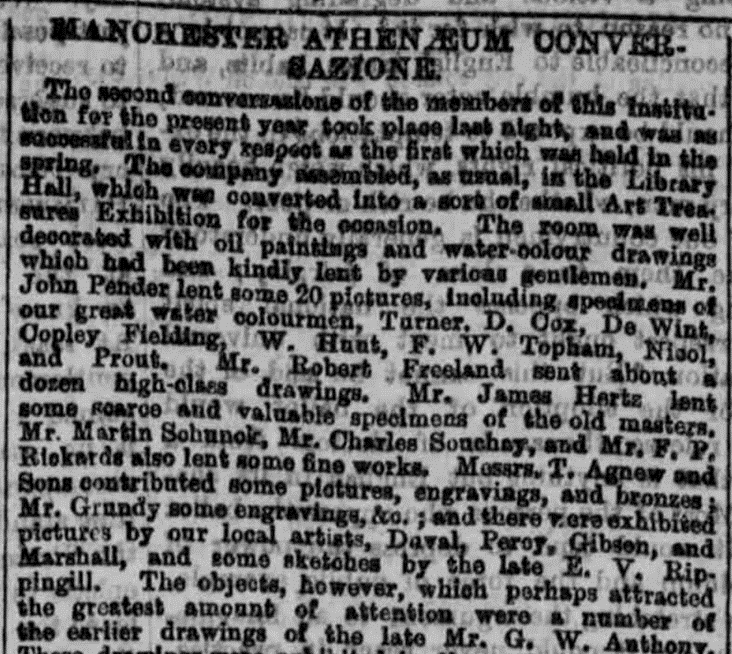

‘Conversaziones’, evening soirées of entertainment for Athenaeum members, stood out for me in my research. Nowhere were the connections between slavery, cotton, industrialisation, and the refined cultural aesthetic that Athenaeum members cultivated made clearer.

Members (most of whom were connected to the cotton economy in some way) and their wives, could view the latest, finest artworks – all donated by friends of the institution – or listen to musical performances as well as recitals and dramatic readings. These evenings symbolised the very “purpose for which the Athenaeum was established”, wrote the Manchester Times in April 1859, reporting on the first conversazione of the year.

Competing Visions of Manchester’s Rise

The Manchester Times also reported on the second conversazione held later that year, detailing the address from the evening’s chair, a John Pender, who had contributed a large proportion of the work on display. Pender, who later became an MP and a knight, was one of the Athenaeum directors and a wealthy fabric merchant with warehouses in Manchester.

In his speech, Pender laid out a celebratory vision of industrial Manchester and its economic and cultural achievements, attributing all credit to the innovation, genius, and bravery of industrialists.

“We live in the centre of the greatest manufacturing industry in the world . . . An industry created in a great measure by the genius, energy, and self-reliance of humble men. What results have sprung from their creation!… The name of Manchester is known all over the world. Our manufacturers are in a great degree the pioneers of civilisation. Let the name be one of honour!”.

Pender continued: “I believe there is no limit to industrial progress. Then it is you, the young and rising men of Manchester, that we, who have hitherto endeavoured to do our duty to our country, must look to advance still further the power, position, and character of commerce. The British merchant’s name is respected all over the world”.

Extract of John Pender’s speech to the Manchester Athenaeum on the 9th December, 1859. ‘Manchester Athenaeum Conversazione’, Manchester Times, 10th December, 1859 – British Newspaper Archive.

Science Museum Group Collection.

It is noteworthy that an evening dedicated to arts and culture was almost entirely introduced through its connection to Manchester’s industrial prowess. What mention there was of the conversazione’s purpose was wrapped up with the industrialism of Manchester, making clear the links between the cultural aesthetic of the Athenaeum and the industry it depended on. Pender urged the audience to enjoy, “literature and art and also feel that the British merchant knows their value, and is ever ready to aid their progress”.

As striking as Pender’s incessant focus on the ingenuity of Manchester’s merchants and manufacturers is his lack of any mention of the importance of the raw cotton which supplied the industry. His words elucidate the too often silent links between the industrial boom of Victorian Manchester, the wealth and high-society culture this afforded, and the labour that both depended upon. At the time of Pender’s speech, 80% of the city’s cotton was planted and picked by enslaved people on plantations in the United States.

Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

It is impossible for Pender not to have known this dark truth. In a lecture described by the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser as “eloquent and heart-stirring”, Sarah Parker Remond had called out the grim source of the cotton industry’s fortunes just two months prior in the same room, possibly to many of the same listeners, inextricably noting the connections between Manchester’s wealth and the system of slavery, in her famous words:

“When I walk through the streets of Manchester, and meet load after load of cotton, I think of those eighty thousand cotton plantations on which was grown the one hundred and twenty-five millions of dollars’ worth of cotton which supply your market, and I remember that not one cent of that money has ever reached the hands of the labourers”.

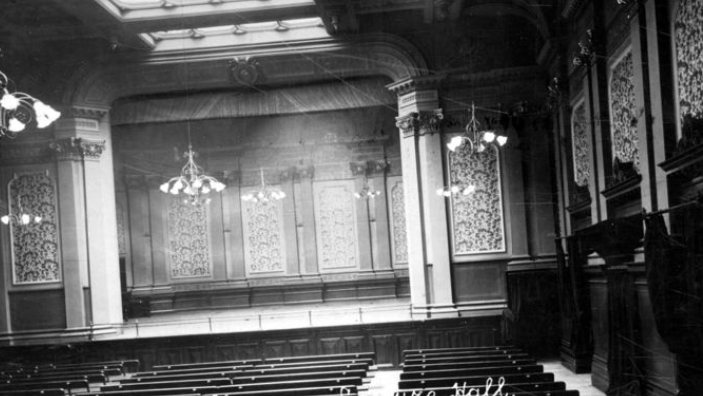

When doing this research, I couldn’t help but wonder what would have been going through Remond’s mind, how she would have felt, lecturing to an audience made rich from the very trade she was denouncing. When I visited the exhibition space in Manchester Art Gallery that used to be the Athenaeum’s lecture hall, I was struck by the grandiosity of the room. It was intimidating.

Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives.

I wondered, how would Remond have felt walking into this large room to a sea of white, mainly male faces, in an environment seemingly so hostile? I noted the statues of the seven muses fanning the high ceiling, symbolising the pursuit of knowledge the elite Athenaeum members were committed to, but only afforded due to wealth cultivated through the labour of enslaved people. Would Remond have noticed this too? Would she also have felt out of place, in a space built upon the proceeds of enslaved labour?

The cotton industry was the backbone of the Athenaeum, as it was its home city’s. My research provides necessary context to the wealth and culture afforded to Manchester’s cotton class and should challenge us to ensure that we consider deeply how our present and future narratives are created and perpetuated.

That Pender’s address, unashamedly and bombastically proud of Manchester’s cotton-driven progress and civilisation, existed in the same space and time as Remond’s searing critique encapsulates the tension between the competing narratives about the origin of the city’s wealth and cultural institutions that continues to this day.

Find out more about Sarah Parker Remond’s time in Manchester

Find out more

Manchester Art Gallery, Sarah Parker Remond Commission.

Hannah Ruddle, ‘COTTON IS KING!’ Sarah Parker Remond, Manchester and the Abolitionist Movement in Britain and America, 1859-1861.

Pender, John, Dictionary of National Biography, 1901.