Edisto Island and McConnel and Kennedy

The invisibilised labour behind Manchester’s mills

LISTEN HERE TO THIS CASE STUDY READ BY THE AUTHOR

This article draws on research supporting The Warp / The Weft / The Wake by Holly Graham

A UAL 20/20 artistic commission working in partnership with Manchester Art Gallery.

Mainstream narratives around nineteenth-century Manchester’s growth into the world’s first industrial city often centre the ingenuity, wealth, and power of the city’s industrial elite and the contributions they made to its culture, politics, and civic life. As a result the legacies of cotton, enslaved labour, and colonialism, which enabled the profits of Manchester’s growing ruling class, are often placed on the outskirts of the historical narrative.

Projects like Global Threads and the Race, Roots, Resistance Emerging Scholars Programme are interrogating the historic links between Manchester’s textiles industry and transatlantic slavery and how these legacies connected to several of the city’s Victorian institutions. This case study has focused on the Manchester Athenaeum and the Royal Manchester Institution, which were both founded, funded, and governed by people who profited from cotton cultivated by enslaved populations.

The Manchester Athenaeum, Commemorative Notice, (Geo W. Pilkington & Co., Manchester, 1903) – Manchester Art Gallery Archive.

By tracing just a few threads from Manchester, the city of cotton, to the United States, this work underscores how the city benefited from the brutal labour of the plantation regime. It aims to elevate the names, voices, and histories of just one of the thousands of communities of enslaved people without whom there would never have been a “Cottonopolis” or the rich cultural institutions that the city Manchester boasts today.

Importantly, this work is contributing to artist Holly Graham’s exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery as part of the 20/20 Project, contributing to our collective reckoning with the injustice, resistance and brutality rooted in Manchester’s history.

McConnel and Kennedy: tracing the cotton

Records in the John Rylands Library are rare in that they allow us to exactly trace raw cotton shipments from five specific plantations and enslavers on Edisto Island in the United States Sea Islands directly to McConnel and Kennedy, one of Manchester’s most prominent cotton manufacturing partnerships. The partners, James McConnel and John Kennedy, were donors to the Royal Manchester Institution, a learned society founded in 1823 by a group of industrialists and artists keen to promote Manchester as a centre for culture and knowledge. The institution’s building, and its collection of artworks, now form Manchester Art Gallery. McConnel and Kennedy were also supporters of the Manchester Athenaeum, a society set up next door to the RMI to promote the arts and learning, also now also part of Manchester Art Gallery.

‘Letter from B. H. Green to McConnel & Kennedy’, Charleston, South Carolina, December 1817 – MCK/2/1/24 – John Rylands Research Institute and Library.

While Mancunians might have a general understanding of “where the cotton came from”, these records allow us to trace tangible links through specific bales of cotton back to the specific plantations where they originated, and the specific individuals whose labour produced them. These detailed and rich stories of communities linked directly to Manchester show us the devastating human cost of the Cottonopolis and offer us insight into the brutal conditions of the plantation regime which funded the extraordinary profits of the city’s wealthy industrial elite.

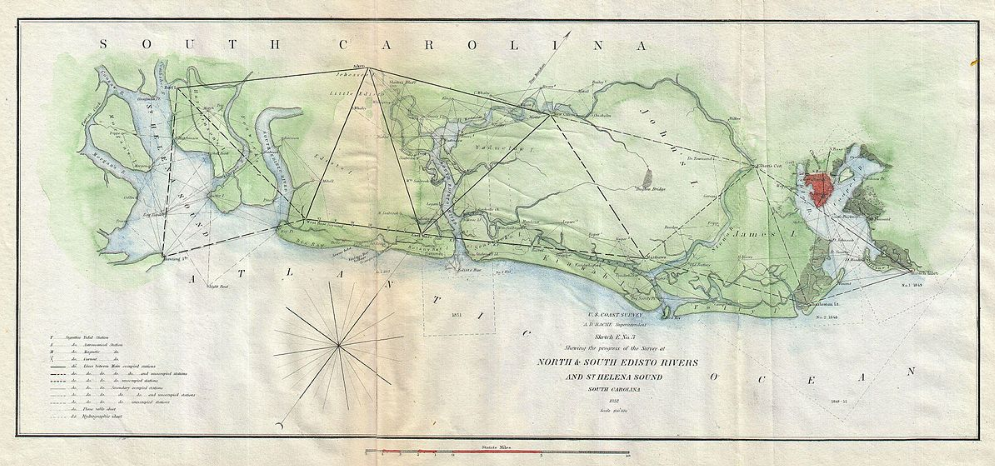

Edisto Island

Edisto Island was historically inhabited by the Cusabo people before European colonisation. When European colonisers first permanently settled on Edisto Island, the land was divided out between planters by the colonial government through a system of grants. The first was given to English merchant Paul Grimball in 1683. This marked the beginning of a period stained by brutal labour, chattel slavery, and profits for planters. Grimball’s plantation was later described as “inferior to none in the province, either for corn, indigo, or rice” in the South Carolina Gazette.

Although records created by enslaved people themselves are rare, we can still develop an understanding of their experiences and lives by drawing on surviving sources, such as newspaper reports, which offer an insight into the horrors of the plantation regime. For example, The South Carolina Gazette published an article appealing for the return of “a young Negro Wench named Die” who ran away from Grimball’s plantation in 1737.

Although the language in the article dehumanises Die and is dominated by the text’s purpose to control and police enslaved communities, it also provides us with information about her appearance and clothing, and highlights enslaved people’s efforts to pursue freedom through escape, one of the various forms of agency and resistance against enslavement.

Until the late eighteenth century, indigo was the primary cash crop produced on Edisto. It commanded high prices, and many planters became extremely wealthy. However, it lost its commercial success after 1774 due to disrupted trade during the American Revolutionary War. The economic void after the decline the indigo trade and the development of the cotton gin led to the rapid adoption of Sea Island cotton, which was highly desired and famed in Lancashire for its long, fine strands.

1852 United States Coast Survey Map of the North and South Edisto Rivers, South Carolina – You can view a hi-res version of this map at Wikimedia Commons.

The gin was a machine which allowed seeds to be removed much more easily from raw cotton, making large-scale production hugely more efficient. As a result, between the 1790s and the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, the Sea Islands, including Edisto, were a centre of a horrific system of brutality against enslaved people based on profitability.

The Civil War and Reconstruction

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the enslaved communities on Edisto Island were greatly impacted. The island became a battleground for the opposing sides, ultimately leading Confederate authorities to order enslavers to evacuate. Planters abandoned their properties and some enslaved individuals seized the opportunity to flee to Union lines for freedom, while the remaining African Americans lived free of their enslavers but unsure of their rights to land and liberty.

The war ended in 1865 with Emancipation from enslavement, and a programme of government reforms, including the enforcement of voting and civil rights, called Reconstruction. Emancipation provided a clear shift in material conditions for newly-freed African Americans on Edisto Island, but this era presented significant new challenges in gaining and protecting freedom, security, and prosperity.

The 1870 Edisto Island census reveals the societal shift that Emancipation presented, with the Black community relieved from the oppressive plantation labour and abuse, allowing for greater autonomy and educational opportunities. Labour dynamics changed markedly: while most men continued to be engaged in agricultural work, women took on household roles, whereas previously under enslavement they were forced to endure heavy field labour. Many children, meanwhile, were now able to attend the newly-founded local schools, a practice previously banned by enslavers.

1870 United States Federal Census, South Carolina, Edisto Island, p. 2 – Ancestry.com (subscription required).

Post-Civil War, land ownership was one of the most contentious and important issues to settle. The Freedmen’s Bureau offered land grants for some newly-liberated enslaved people on former plantation land but, many of these grants lost value rapidly, leaving freedpeople vulnerable. Communities organised themselves to fight for their vision for life after Emancipation, exemplified by a petition from the Edisto Island committee of freedpeople to President Andrew Johnson protesting the return of land ownership to former enslavers, signed by community leaders Henry Bram, Ishmael Moultrie, and Yates Sampson.

“Here is were we have toiled nearly all Our lives as slaves and were treated like dumb Driven cattle, This is our home, we have made These lands what they are. we were the only true and Loyal people that were found in posession of these Lands. we have been always ready to strike for Liberty and humanity yea to fight if needs be To preserve this glorious union. Shall not we who Are freedman and have been always true to this Union have the same rights as are enjoyed by Others?”

Extract from letter: ‘Committee of Freedmen on Edisto Island, South Carolina, to the President’, Oct 28th 1865 – Full text available from Freedmen and Southern Society Project, University of Maryland.

The story of Jim Hutchinson

A well-documented story of a formerly enslaved person on Edisto Island is Jim Hutchinson, who was born in about 1836 on Peter’s Point Plantation and lived alongside 225 other enslaved people. Jim was the son of an enslaved woman, Maria, and her enslaver Isaac Jenkins Mikell. He witnessed numerous significant historical events on the island, experiencing the brutality of enslavement, the turmoil of the Civil War, and the false dawn of the Reconstruction Era.

Post-1865 Jim was heavily involved in activism, taking advantage of the new laws protecting his right to vote and run for office. He played a pivotal role in the community, co-founding a Black-owned ferry company, and significantly, in 1872 organising a land purchase cooperative, acquiring 234 acres. Land ownership was a profound form of resistance that challenged the entrenched power dynamics and racial hierarchy that continued after the legal abolition of enslavement. For formerly enslaved communities, owning land was crucial for ensuring security and future prosperity. Without land, they would remain reliant on oppressive, wealthy landowners for income.

In 1885, Jim was murdered by a white man, exemplifying how the system of racial oppression was reimposed through violence and terrorism despite the abolition of enslavement. Jim’s increasing successes acted as a reflection of the growing agency and autonomy of the Black community, contradicting the white supremacist ideology, which was foundational to the plantation regime. This made Jim a target.

His murder unveils the societal upheaval during the Reconstruction period. Despite the abolition of enslavement, poverty, land struggles, racial violence and disenfranchisement continued. Former enslavers wanted to maintain the racial hierarchy and power imbalance which led to Jim Crow racial segregation laws being established and voting rights suppression. These attempts to maintain control over land reflect the continued demand for cotton post-slavery which served to further entrench the economic struggles of the Black population.

After Jim’s death, his son Henry continued the family legacy – building Hutchinson House which stands today as the oldest identifiable post-Civil War house associated with the Black community. In 2022 Greg Estevez, the great-great grandson of Henry Hutchinson, wrote a book called Edisto Island: The African American Journey which combines the oral histories passed down through his family alongside the physical remnants of Gullah traditions, originating in West Africa, to highlight the resistance of the predominantly Black community post-war. Estevez’s book celebrates the survival of these customs and their significance in strengthening the community’s unified resistance against oppression.

By using the original records to trace the threads of McConnel and Kennedy’s cotton from Edisto Island to Manchester, we uncover a profound narrative of resilience and resistance amidst oppression. From the early exploitation of Sea Island cotton to the turmoil of the Civil War, Reconstruction, and segregation, Edisto Island’s African American community faced immense challenges that did not end with Emancipation, yet they demonstrated remarkable agency and perseverance.

Credit: Mindy Friddle, “Straight Outta Edisto”, 28th April, 2022.

Today, along Highway 174, a bottle tree memorial serves as a poignant reminder of past brutality, embodying the Gullah people’s belief that evil is trapped within the blue-painted bottles, unable to escape the darkness, only to be vanquished by the dawn’s light. As evidenced by Greg Estevez’s work, the community continues to honour its Gullah traditions and resilience, underscoring a narrative of strength and resilience against historical odds.

Find out more about the connections between McConnel and Kennedy and South Carolina and the experiences of those enslaved in cotton cultivation

Find out more

Greg Estevez, Edisto Island: The African-American Journey (2019) – available as an e-book.

LISTEN – Oral Histories of Edisto, Edisto Island Museum.

A Cabin Story, National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Joe Sugarman, ‘The House That Hutchinson Built’, Preservation (Winter, 2021).