Fabric of Injustice: Unveiling the Lives of Enslaved Families at Turner’s Hall

This article draws on research supporting the co-curation of The Penistone Cloth: Textiles and Slavery – From the Pennines to Barbados and Beyond exhibition held at Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery as part of the British Textile Biennial

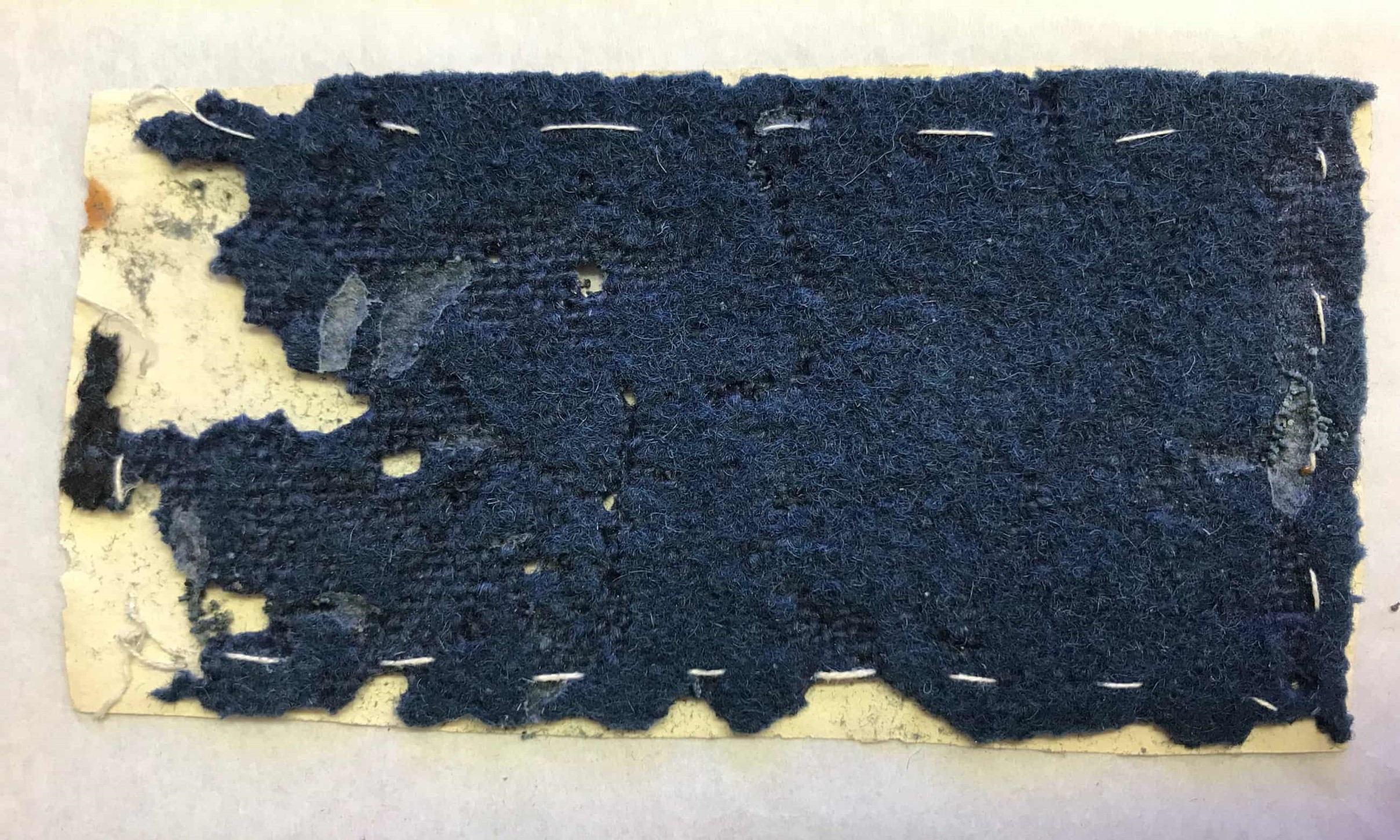

Turner’s Hall is a historic plantation house that dates back to the early 18th century, nestled in the picturesque St Andrew Parish in Barbados, with 50 acres of valuable woodland. This estate was just one of hundreds in Barbados but, uniquely, we have a surviving physical link to this place and its community. Records show that this is where the penistone cloth sample at the heart of our exhibition was sent to clothe those enslaved on this sugar plantation.

Barbados National Trust, courtesy Barbara Taylor.

Built during the era of European colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade, the walls of Turners Hall bear silent witness to the enduring legacies of both oppression and resilience. In this blog post, we will embark on a journey through the history of the estate, delving into the many records to unearth and re-weave fragments to explore the experiences and story of an actual enslaved family.

One Family’s Profits from Enslaved Labour at Turner’s Hall

Inherited through marriage with Sarah Perrin, Sir William Fitzherbert became the owner of Turner’s Hall in the 1750s. We know a great deal about the Fitzherbert family’s story because of their wealth and prominence. Their family records, archived in the Derbyshire Record Office, are a clear example of the way in which the legacies of profits, power, and ownership of enslaved people are embedded throughout the UK.

The grandeur of Turner’s Hall was made possible through the forced labour, trafficking and torture of hundreds of individuals and families of African descent. At the time of inheriting the plantation, there were around 150 enslaved people held there. Turner’s Hall plantation operated profitably for its absentee owners for decades.

The estate was run by a series of managers and overseers while its owners had minimal involvement in day-to-day management, residing in wealth in England. Following Sir William’s death in 1791, the estate transitioned to his son, held in trust by Lady Sarah Fitzherbert.

Science Museum Group Collection.

While British slavery expanded across the Caribbean, Barbados was often remarked to be exhibiting some of the highest levels of systemic violence, brutality, and racialised inhumanity. Enslaved labourers were responsible for constructing the plantation house, its accompanying outbuildings, and the sprawling sugar cane fields that surrounded it. Their physical contributions were essential in shaping the landscape and architecture of Turner’s Hall.

The exploitation of enslaved people extended far beyond construction. The majority of labour was directed to the cultivation of crops, particularly sugarcane, which was the mainstay of the Barbadian economy during the colonial period. This labour-intensive crop required gruelling work, from planting and harvesting to processing, packing, and transporting the sugar, as well as many skilled and craft activities vital to the plantation economy.

“If a Mill-feeder be catch’d by the finger, his whole body is drawn in, and is squees’d to pieces, If a Boyler gets any part into the scalding Sugar, it sticks like Glew, or Birdlime, and ’tis hard to save either Limb or Life.”

Description of some of the hazards faced by enslaved people forced to work on sugar plantations. Cited in Bridenbaugh and Bridenbaugh, No Peace Beyond the Line: The English in the Caribbean, 1624-90, 1972, p. 301.

Family Lives of the Enslaved at Turner’s Hall

While family histories of rich enslavers are very well documented, the vast majority of enslaved families and communities are absent and erased. While the lives of enslaved individuals at Turner’s Hall were shaped by work, they each had experiences that extended far beyond their forced labour.

Families were central to their lives, and they created a sense of community within the harsh conditions of slavery. Enslaved families endured the hardships of plantation life together, providing emotional support and a sense of belonging.

The same records of the Fitzherbert family’s profits from Turner’s Hall plantation also open a window onto the lives of the 139 individuals who lived on the plantation in 1759 and the 166 held there in 1771. These lists can shed light on the wide range of jobs, skills and relationships that enslaved people had.

Reviewing these lists, we can pick out 7 individuals, Great Robin, Murriah, Nanny, Cuffey, Robin, Landah and Sarey; a family.

Great Robin and Murriah parented 5 children: 2 girls and 3 boys. Their daughter Nanny had three sons of her own during the 1780s. Records also show two nephews of Great Robin, Larrick and Little Robin. Sadly the exact ages of most of the family not recorded. Rather, their value is known, expressing how the commodification of their lives was the main focus of collecting this information.

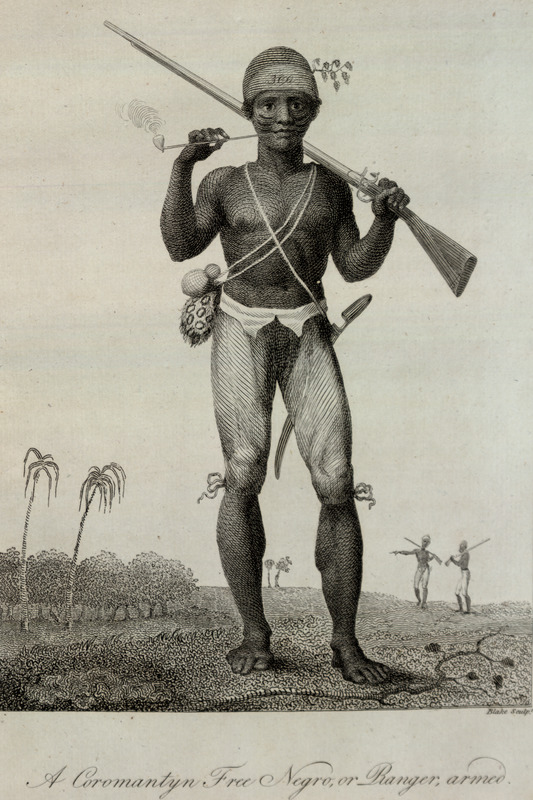

Great Robin, the father, was Head Watchman in 1771 and a Ranger in 1780. A Ranger was a head officer among the enslaved workers involved in policing entry and exit to the estate.

He also acted as a Boiler, a very highly skilled job which was also extremely dangerous. The Boiler oversaw the reduction and purification of sugar cane juice through a meticulous process.

Controlling the transitions between copper vats, the Boiler determined the optimal stages for the juice, progressively transforming it into muscovado sugar. With great expertise, the Boiler gauged the crystallisation point, adding lime juice to temper the mixture before transferring it to a cooling vat for the final product. In this way, the Boiler played a crucial role in crafting high-quality muscovado sugar from the original cane juice.

Through having a highly skilled job, Robin was seen as an ‘elite slave’ with high value, often receiving enhanced rations, clothing, or healthcare when needed. There are records which describe a situation where Robin was ill, so the plantation overseer provided him with two chickens to help him to recover. This same treatment was unlikely to be given to those working out in the field.

Murriah, the mother, was a nurse, a job that was reserved for enslaved women. Murriah was responsible for attending to the health needs of enslaved individuals and, possibly the plantation managers’ families. From the records, it can be seen that Murriah was working “under” Rose Olton, an enslaved elder on the plantation.

This means Murriah and Rose had a very close working relationship where Murriah likely learned a great deal from Rose’s expertise – likely. assisting with childbirths and learning, employing and preserving traditional African healing practices.

The 1780 records also show that Landah, a “small boy” in 1780 was working with the estate Mason in 1789. Robin’s high-status role was likely important in securing his son’s apprenticeship in learning the valuable skills of stone working that would afford him a future role away from the heavy fieldwork that most of the enslaved community would have to endure.

The varied roles within enslaved communities provide a glimpse into the complexity and diversity of experiences among those subjected to slavery and the depth of skills and expertise they developed and passed on. Yet, despite these varied roles, the underlying injustice and dehumanisation of slavery remained a common thread, shaping the lives of individuals and families like Cuffey, Sarey, Great Robin, Murriah, and Nanny in profound and often devastating ways.

In reflecting upon the intricate history of Turner’s Hall, one cannot overlook the profound echoes of suffering and resilience etched into its very foundations. The struggles and lives of those enslaved individuals, encapsulated within the walls of this plantation, paint a vivid yet harrowing portrait of a past marred by exploitation and injustice.

Among the haunting legacies is the use of penistone cloth, a solid fragment that survives connecting the Pennines intimately to those who toiled on these lands. Each thread of this fabric, adorning the bodies of the enslaved, carries with it a silent testimony to the erasure of identity and the commodification of human lives during an era stained by the brutality of slavery.

Find out more

Online

Turner’s Hall Estate, Legacies of British Slavery database.

Cryssa Bazos, “Sugar Production in 17th century Colonial Barbados“.

“Bussa’s Rebellion: How and why did the enslaved Africans of Barbados rebel in 1816?“, National Archives.

Articles

Justin Roberts, “Uncertain Business: A Case Study of Barbadian Plantation Management, 1770–93“, Slavery and Abolition, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2011, pp. 247-268.

Hilary McD. Beckles, “Enslaved Women and Anti-Slavery in the Caribbean” in Claire Midgley (ed.), Gender and Imperialism, Manchester, 2017.