hillsborough and manchester

Tracing profits and recovering lives in the archive

LISTEN HERE TO THIS CASE STUDY READ BY THE AUTHOR

This article draws on research supporting The Warp / The Weft / The Wake by Holly Graham

A UAL 20/20 artistic commission working in partnership with Manchester Art Gallery.

In April of this year, I made a visit to the Cambridge University Archives to research the Greg Family and the Hillsborough Estate that they owned in Dominica. Stepping into the archives for the first time was breath-taking. The importance and nobility of the building was outstanding, evoking a sense of awe that I had rarely experienced before.

The imposing architecture, steeped in centuries of knowledge and discovery, was both inspiring and overwhelming. I would be lying to myself if I didn’t admit that I felt a twinge of self-doubt and a sense of not belonging. The weight of history pressed down on me, a researcher amidst the overbearing legacy of scholars who had walked these halls.

The Greg Family and Their Legacy

My research focused on the Greg family, prominent figures in the history of the cotton industry and important members and major donors to the Royal Manchester Institution, a society founded in 1823 by a group of industrialists and artists keen to promote Manchester as a centre for culture and knowledge. The building, and the institution’s art collection, are now part of Manchester Art Gallery.

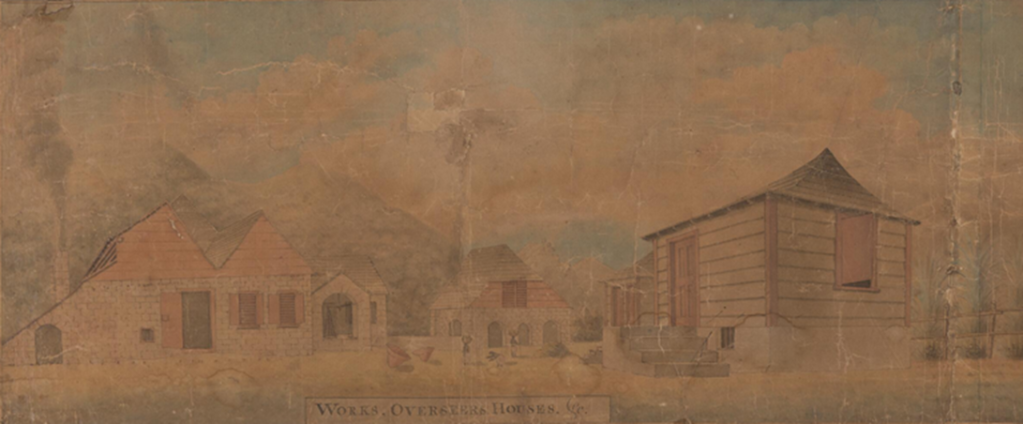

The Gregs owned Quarry Bank Mill in Styal, near Manchester, and Hillsborough Estate, a sugar plantation in Dominica. The juxtaposition of their enterprises — one in the heart of industrial England and the other in the colonial Caribbean — demonstrate within one family’s activities the inseparability of Manchester’s rise from transatlantic slavery and their entwined legacies.

Slave-grown cotton imported to Britain that was spun and woven into cloth at Quarry Bank Mill was sent to Hillsborough for clothing and blankets to be used by the people enslaved on the plantation. This material connection between the mill and the plantation illustrates the broader economic and human networks that underpinned the Industrial Revolution and the colonial enterprise.

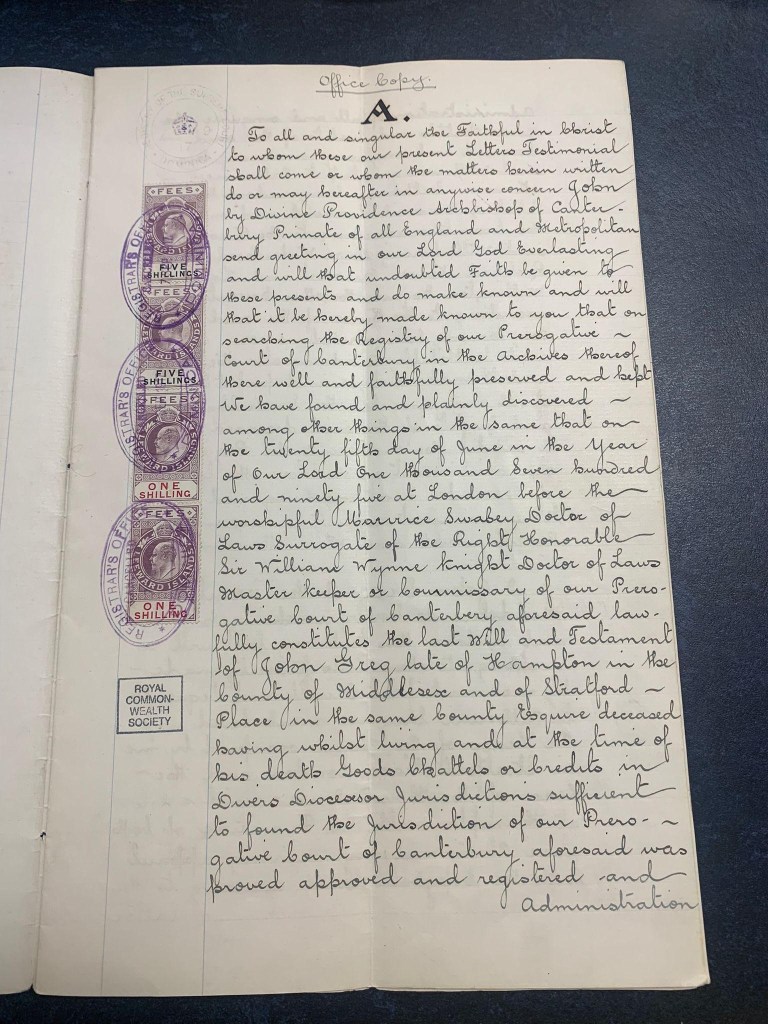

In the archives, I uncovered two significant documents: the Will of John Greg (1716-1795) and the Inventory of Enslaved Persons and Property at Hillsborough Estate.

Credit: Arlington James, ‘How ‘compromised’ was the Hillsborough bridge?’, Dominica News Online, Friday, January 21st, 2022.

The Will of John Greg

The Will of John Greg is a fascinating document that provides insight into the transatlantic connections of the Greg family. John Greg passed down two estates in Dominica to his nephews, Samuel Greg of Manchester and Thomas Greg of London. This transfer of wealth and property maintained the fortunes and high standing of this family, and offered continuing profits that supported the development of the cultural fabric of Manchester, including through considerable donations and support to the Royal Manchester Institution.

National Trust Images from Art UK.

When slavery was abolished in the British Empire, the Greg family received over £5,000 (the equivalent of almost £600,000 today) in compensation for their “loss of property” upon the emancipation of the enslaved, whilst those formerly held in bondage received nothing. This wealth sustained the Gregs across generations and they remained owners and beneficiaries of Hillsborough estate well into the twentieth century.

The Inventory of Enslaved Persons at Hillsborough Estate

The second document, the Inventory of Enslaved Persons, was particularly striking to view and handle. It lists the names, roles, ages, genders, and physical descriptions of the enslaved individuals on the Hillsborough Estate in 1818. Encountering this inventory was a sobering reminder of the human cost of the Greg family’s wealth. Each name and description brought to life the individuals who had been reduced to mere property in the eyes of their owners.

The inventory was the most compelling document for me. In 1818 there were 71 males and 68 females, bringing the total community to 139, including children. Listed alongside the human property of the Gregs there were 11 mules and 31 cattle used for transportation, milk, meat, and manure for crops.

The inventory lists the names, role and physical description of each person in the community. The purpose of this document was to better manage production and profits and enforce and count ownership, further dehumanising the individuals listed.

Humanising the Past

However, when we view these oppressive documents through a new lens, it offers an opportunity to humanise the lives of those enslaved at Hillsborough and provides a glimpse into their daily experience. We are able to understand more about the variety of tasks they were forced to carry out and skills that they held; cooks, field workers, carpenters — and the detailed descriptions make it easier to paint a vivid picture of individual people. The document acts as a poignant reminder of the resilience and humanity of those who endured the brutality of slavery.

For instance, taking two individuals from the document, Sabrina and Matilda (ages unknown) were both “field able” women who worked long, gruelling hours of heavy labour, planting, digging, clearing and harvesting in the field.

Inventory of enslaved persons and property, Hillsborough Estate, 1818 – Cambridge University Library – GBR/0115/RCS/RCMS 266.

This inventory also lists items that are held in different areas of the estate, including in the cellar below the house, including two mason axes, two hammers, and two mallets. The list of tools details a mill wedge which was used to power water-powered mills, a crop cut saw, typically used to cut timber, and a hand and whip saw file to resharpen saw teeth.

Further information about tools is found in the estate Account Book, which details different supplies that were shipped to Dominica from Britain to aid with the running of the estate. For instance, a box containing 36 mill wedges, two crop cut saw files, and six hand and whip saw files, amongst other items.

Account book of Cane Garden and Hillsborough Estates, 1820-8 – Cambridge University Library – GBR/0115/RCS/RCMS 266.

By cross-referencing this information with evidence from other sources, we can identify that these items would have been handled and used daily by Smart and Sharp, who we find listed in the inventory of enslaved persons as Head Carpenter and Carpenter. They would have been responsible for repairs, maintaining the complex industrial mill machinery, and making useful wooden items.

These individuals would have been highly skilled in craftsmanship, innovation, and creativity. On the inventory, Smart is listed as “old and blind”, but his continuing senior role is a testament to his knowledge and skills being essential to directing complex labour at Hillsborough and passing those skills down to younger apprentices and craftsmen.

Map of Hillsborough – Cambridge University Library – GBR/0115/RCS/RCMS 266/1.

Those same and similar tools would also have been used by Dick, William, and Cypress, the estate coopers, whose job was to make the barrels which were integral to shipping Hillsbrough’s produce to Britain. Another surviving archival item from Hillsborough is a Sales Book that details shipments of sugar and rum produced on the estate.

A single consignment on a ship called the Ealing Grove in September 1820 of 54 barrels sold to London merchants Sutton and Davies and H. H. Browne was worth £2,332, which in today’s money would be around £127,825. This is just one of thousands of shipments from Hillsborough during its time as a site of enslavement. All of those profits went to the Gregs.

The Ship ‘Ealing Grove’ – BHC3299 – Royal Museums Greenwich – Wikimedia Commons.

Reflections on the Research Process

Being part of this research project has been a deeply reflective experience. It has made me acutely aware of the privilege and responsibility that comes with accessing and interpreting historical documents. Walking through the grand halls of Cambridge University, I felt a renewed sense of purpose. This research was not just an academic exercise but a vital act of remembrance and acknowledgment. Furthermore, I am now more conscious and reflective when I enter spaces as to where the funding comes from.

My interest in this project was partly personal. Having lived in Manchester for six years, I was intrigued to understand the origins of the city’s cultural landmarks, particularly Manchester Art Gallery, which is such a staple of the city’s cultural scene. Uncovering the connections between the Greg family’s wealth and the funding of cultural institutions in Manchester added a new layer of complexity to my understanding of the city’s history.

My time at the Cambridge University Archives was a journey through history that was as enlightening as it was harrowing. Discovering the stories of the Greg family and the enslaved individuals on the Hillsborough Estate was a profound experience that underscored the interconnectedness of our histories and the importance of remembering and acknowledging all aspects of our past. This research has deepened my knowledge of the cotton industry and the enduring impact of the Industrial Revolution and colonial enterprise on our world today.

Explore more archival records that allow us to better understand the experiences of enslaved people in the Caribbean connected to the growth of Britain’s textile industry

Find out more

‘Samuel Greg’, Legacies of British Slavery database.