West African Science,

Technology,

Innovation, and Industry

The view of Africa without science is partly due to racist and misinformed perceptions about the meaning of these terms and the attempt to universalize definitions and experiences from the Global North (also known as the West), particularly as these unfolded during the Industrial Revolution . . . Regions today considered part of the Global South played a significant role in understanding the global history and archaeology of science, technology, and innovation.

The use of different apparatuses and methods of recording, reading, and measuring aspects of technical processes should not take away from what ancient Africans were capable of achieving. As producers of science and technology, they achieved technical feats, some of which are still beyond modern technology.

In this section we look at our two key questions:

Where did the industrial revolution take place?

Whose labour, skills, and knowledge drove industrial development, innovation, and production?

Through a focus upon artefacts, archaeology, and primary sources concerning metalworking technology, skills, and trade in West Africa from around 1500 to 1800 – a period marked by an expansion in metalworking shaped by access to raw materials imported from Europe.

By drawing on these sources, we see that West Africa was firmly part of the early industrialising world, drawing on centuries of technological developments and practice, and leaving remains of industrial sites and landscapes.

The skills and material demands of West African metalworkers and traders shaped the industrial practices of founders in Britain and Europe and also created a manufacturing boom across the region, with processes and relationships to raw material production very similar to those of component makers in “industrial” Britain that persisted into the 20th century.

Download Classroom Resource Case Study on African Science, Innovation, and Metallurgy

Igboland

1750s

Although first-hand written accounts of West African metallurgy in this period are hard to come by, one of the most famous works written by an 18th century African writer, Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative, includes an account of his enslavement by a goldsmith in Igboland (in today’s Nigeria) following his first kidnapping and trafficking:

“This first master of mine, as I may call him, was a smith, and my principal employment was working his bellows, which were the same kind as I had seen in my vicinity.

They were in some respects not unlike the stoves here in gentlemen’s kitchens; and were covered over with leather; and in the middle of that leather a stick was fixed, and a person stood up, and worked it, in the same manner as is done to pump water out of a cask with a hand pump.I believe it was gold he worked, for it was of a lovely bright yellow colour, and was worn by the women on their wrists and ancles.”

Equiano’s account also hints at some of the important roles that metalworking played in economy and culture – with gold being used as adornment and jewellery, to symbolise status. Metal goods also acted as a store of value and an investment and were often usable as currency beyond their primary function.

Benin Bronzes

1600-1800

Above – Queen Idia – DATE

Below – next figure – DATE

Some of the most famous (or infamous) examples of West African metalworking are what are known as the Benin Bronzes.

These extraordinarily detailed sculptures and scenes were created between 1600?? And 1800?? And collected by successive generations of Obas (rulers) of the Kingdom of Benin, which is today part of Nigeria.

The and sheer number length of time across which these objects were produced shows us how deeply embedded and long running these skills were passed across time to new generations of craftspeople who incorporated their own innovations and artistic interpretations.

In just a small selection of images shown here we can see direct portraiture of important individuals, such as Queen Idia, as well as scenes depicting symbolic figures, replete with detailed representations of costume and symbolic items worn and displayed by figures depicted.

Particularly notable is the left-hand scene below, depicted a Portuguese merchant, not only portraying dress and weaponry but surrounded by manilas – a key imported metal source from Europe that acted as both currency and raw material for growing industrial production.

Scientific analysis has shown that most of the Benin Bronzes themselves were made using brass imported from the Rhineland in Germany, possibly in the form of manilas, that were melted down and cast into the intricate designs we now see.

Alongside goods like ivory and gold, the majority of these imported metal sources were exchanged for enslaved persons trafficked to the coast by African traders and states involved in Atlantic commerce.

The Benin Bronzes have a controversial history. They were brought to Britain in 18?? as booty following a military expedition against the Oba of Benin.

They were distributed over time into collections of museums and galleries across the UK and more widely. ?? objects are held at the British Library, ??? in ??? other collections

In these museums and collections, they joined objects collected from across the world as part of a practice of ethnography and categorisation inseparable linked and drawing upon colonialism

Much work has been conducted and is currently underway exploring ways in which returning the objects to their source regions may be facilitated, while also scholars, particularly those from West African, alongside communities work to investigate and understand and interpret the objects and their histories more accurately.

An Industrial Collection?

While that vital work across many projects and strands continues, from the point of view of our approach in the Black Industrial Revolution project, we would pose the question to institutions holding these type of objects of: What would it mean to think of these as an industrial collection?

Rather than hiving off these objects and their production as “Other” and an ethnographic collection, how would our ideas about science, technology, skills, and innovation in West Africa during this period be challenged or developed by thinking of these as industrial objects and production alongside objects made in the UK and elsewhere during the same period?

What opportunities for educational and engagement and participation projects touching on skills and innovation could be developed from this type of approach?

This also helps to draw upon scholarship across decades, not just on metalworking, but a wide range of industrial and craft production that reframes a focus on scientific practice in West Africa:

Dr. Omotoso Eluyemi . . . declared on many occasions during his lectures that “our ancestors were material scientists.” . . . This oft-repeated statement was meant as a counterpoint to the then-popular view that the glass bead makers in Ile-Ife were importing glass from Europe and Islamic world and remelting the glass to make beads between 11th and 15th centuries. But until recently, the geochemical evidence needed to exorcise this ghost of Eurocentric thought about Africa’s indigenous technological skills was not available.

Akinwumi Ogundiran and O. Akinlolu Ige, ““Our Ancestors Were Material Scientists”: Archaeological and Geochemical Evidence for Indigenous Yoruba Glass Technology”, Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 46(8) (2015) pp. 751–772.

More than just products

Iron

Wide range of metals worked with great skills bronzes often brass (copper and zinc), gold, key product of the industrial revolution was iron and was key in drawing West Africa as part of the industrial world of 18th century.

The creation of usable iron implements requires multiple processes –

first mining or sourcing of ores – raw materials

Then you need to use a furnace to separate out and refine the metals

Before finally you can begin working the metal into usable goods

All of those key processes are traceable over 1,500??? Years in Africa – connection with European trading networks was not the beginning of African ironworking or metalworking – connection to these wider markets and raw materials was into a complex and highly-specialised and developed part of economic and social life which, as we will see, African traders, states, and metalworkers had very specialised and specific demands of and fitted into their needs and preferences

Industrial Landscapes – Furnace Archeaology

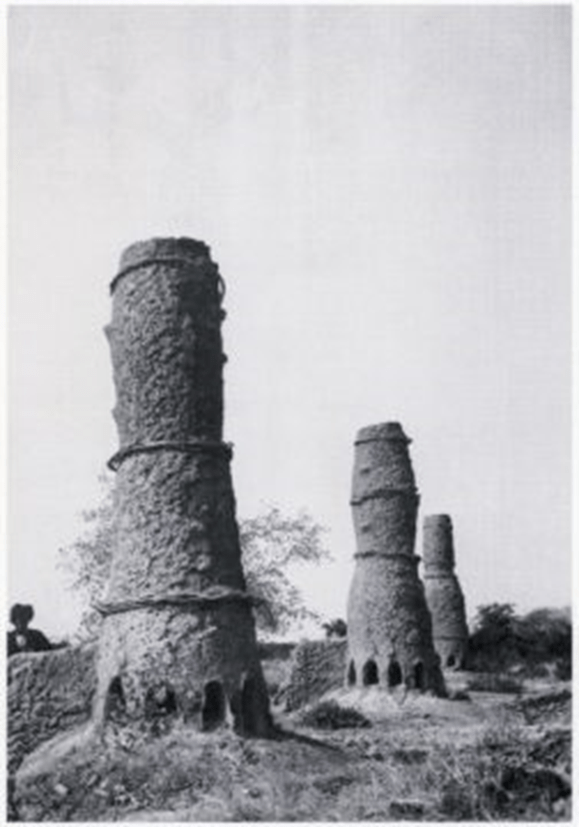

Seno, Burkina Faso

Earthen smelting furnaces in the Seno plain below Segue, Burkina Faso, 1957 – In Hélène Leloup, Dogon Statuary (Strasbourg: Daniele Amez, 1994)

Tiwêga furnace, near Kaya,

Burkina Faso

Ancient Metallurgical Sites of Burkina Faso

Bassar, Togo

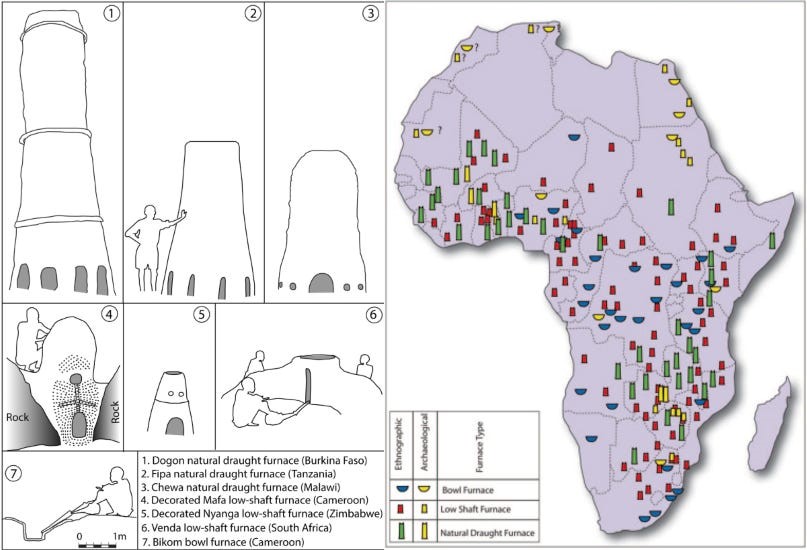

Examples of African bloomery furnace types (by F. Bandama), Approximate distribution of bowl, shaft, and natural draught furnace types in Africa. (by S. Chirikure).

Historical Accounts of African Metalworking Technology

West Africa as part of the industrial world

Accounts from euro observers not only first hand evidence of metalworking and high quality and skill

Presence of Europeans indicate that West Africa was part of global trade network

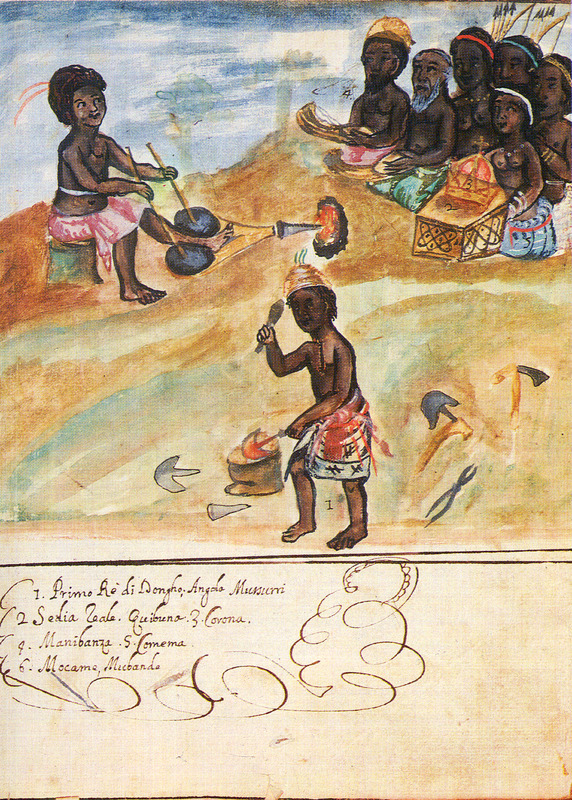

Kingdom of Ndongo

1650s

Foreground shows the legendary first king of Ndongo, Angola Mussuri, forging weapons and tools; in background (left) the use of bellows and (right) royal councilors, all named and guarding a Christian crown.

earliest European records of African metalworking

Barraku, Windward Coast

DATE

Dutch traders – link to article / original source –

they know ‘how to work [it] well, and make all Kinds of Arms or Weapons for themselves’

Gold Coast

DATE

Cape Three Points – description of ironworking and production of tools and weapons – LINK / original source

‘Their iron is much harder’

an agent of Denmark’s Vestindisk Guineisk Kompagni observed after examining the spears carried by warriors on the Gold Coast. –

LINK to article/original source

Very precise specifications for quality, type, size of metal imports – expertise

shaped the industrial processes and products in Britain to the demands of African metallurgists

Benin Bronzes made from German rhineland brass – transported in form of manilas – intricate wax moulding techniques

Access to raw materials led to manufacturing boom making components, tools, weapons, range of goods

Techniques make high quality

Voyage iron had to be made to precise specifications: African traders demanded iron of the correct dimensions, iron of the correct weight, iron with the proper finish, and iron that bore recognisable stamps (‘marks’) attesting to its provenance. Voyage iron that did not meet the exacting requirements of African buyers would find no sale.

‘These people begin to aske for iron barrs and I have a great many but they do not like them, for they must all be marked and no flaw’s in them’

RAC’s agents on the Gold Coast wrote in 1683

‘iron for the Guinea coast’ had to be ‘entirely smooth and soundly forged’, a ‘made according to the measurements which the blacks there demand’.

Dutch supplier of the 1660s LINK/REF

The correct length of voyage iron or Guinea iron is about 11 feet, and of such weight that 18, 19 or 20 bars of it make 5 cwt or 76 to 80 bars in a cask of 20 cwt. It must be smooth and well forged. There is much discussion when there are cracks along the edge of the bars … The buyers in England take great offence at this.

A Swedish observer of the 1670s LINK/REF

Europeans suppliers of raw materials to African manufacturers

Download Classroom Resource Case Study on African Blacksmiths in the Industrial Revolution

Where did the Industrial Revolution take place?

The idea of the Black Industrial Revolution shrinks the distances between sites of industrial production to see them as related spaces happening simultaneously as a single, inseparable phenomenon – not as something that happened in one place in isolation from the rest of the world but part of an ongoing conversation and in response to developments, skills, demands, and practices developed by a global cast of engineers, craftspeople, and manufacturers.

As global movements in goods and people grew, West Africa was part of the industrialising world, with new manufacturing techniques and increased production of metal tools, weapons, components, and items creating economic and social changes.

When it came to manufacturing, the key trade demand for imports from Northern Europe was for raw materials, rather than tools or non-gunpowder weapons. West African states and economies had their own skilled metallurgists who made sophisticated agricultural implements, craft tools, weapons and ceremonial and cultural items for specialised local markets – indeed the metalwares they made were admired by European traders as harder and stronger than their own.

It would be preferable, in fact, to jettison that core-periphery polarity and to think instead of networked smelting zones and manufacturing districts that traded raw metals, semi-manufactured articles, and consumer goods in ways that were multidirectional.

Use of foundries reduced through access to metal from Britain and northern Europe

Type of smithing and component making activities very similar to many those going on in Europe – for example Black Country nails and chain making carried on well into 20th century

Relationship of materials to foundry and the techniques and technologies very similar – difference is only really distance and fuel

types of tools and components different because access to coal or coke rather than charcoal

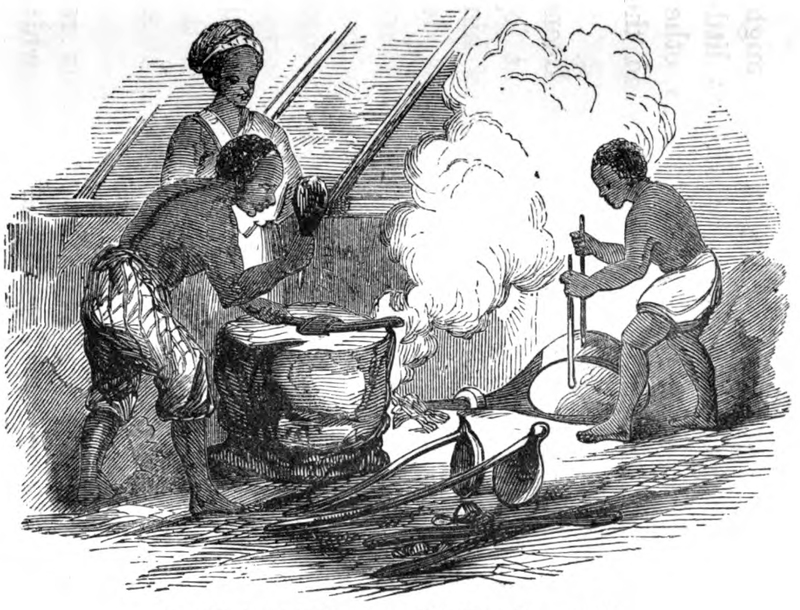

A Female Nail Maker Black Country, England – 1889

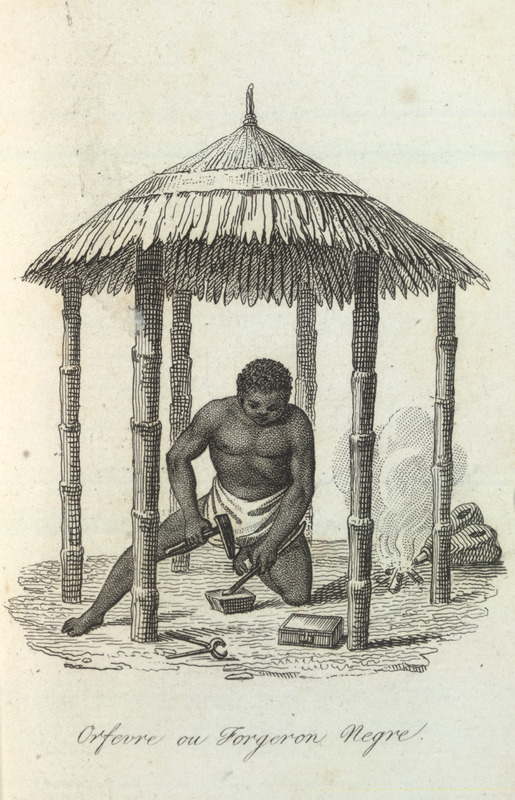

Blacksmith at Work, Senegal – 1780s

A Male Chain Maker and Boy on bellows, Black Country, England – 1889

The Blacksmith’s Forge at Osiele, Nigeria, 1860s

Oumalokho,

Mali-Cote D’Ivoire border

1892

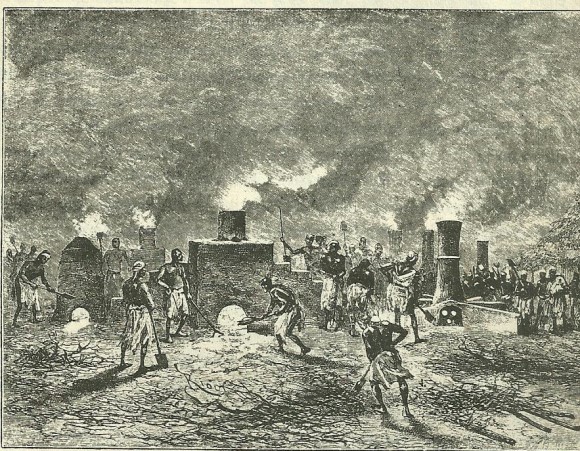

Images are important in shaping our ideas about the past. We end this section with an illustration made by French artist Louis Binger in 1892 of a large iron smelting complex at Oumalokho, near the border of Mali & Cote d’Ivoire.

With similar motifs depicting glowing furnaces and darkened skies to illustrations of manufacturing processes in Britain and Europe this drawing of an African industrial scene challenges us to think again about how we imagine histories of skills and labour.

Explore the key themes and resources of the Black Industrial Revolution here:

Educational Resources

Where Next? – Get in Touch

Team & Credits